Li Juan: A Writer's Journey to the Altay, Northern Xinjiang

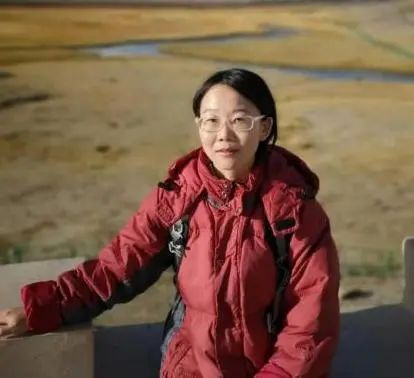

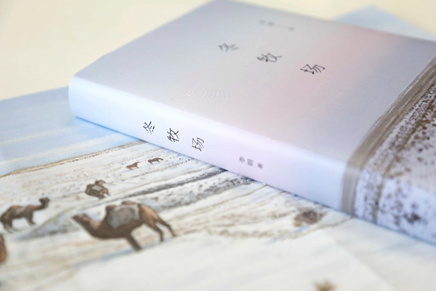

Li Juan, born in 1979. Winner of The People's Literature Award and Lu Xun Literature and Prose Award. Widely regarded as one of the best narrative nonfiction writers of her generation. Publications include Nine pieces of Snow, The Corner of Altay, My Altay, Please Sing Aloud While Walking at Night. Winter Pasture is considered to be her most popular and representative work.

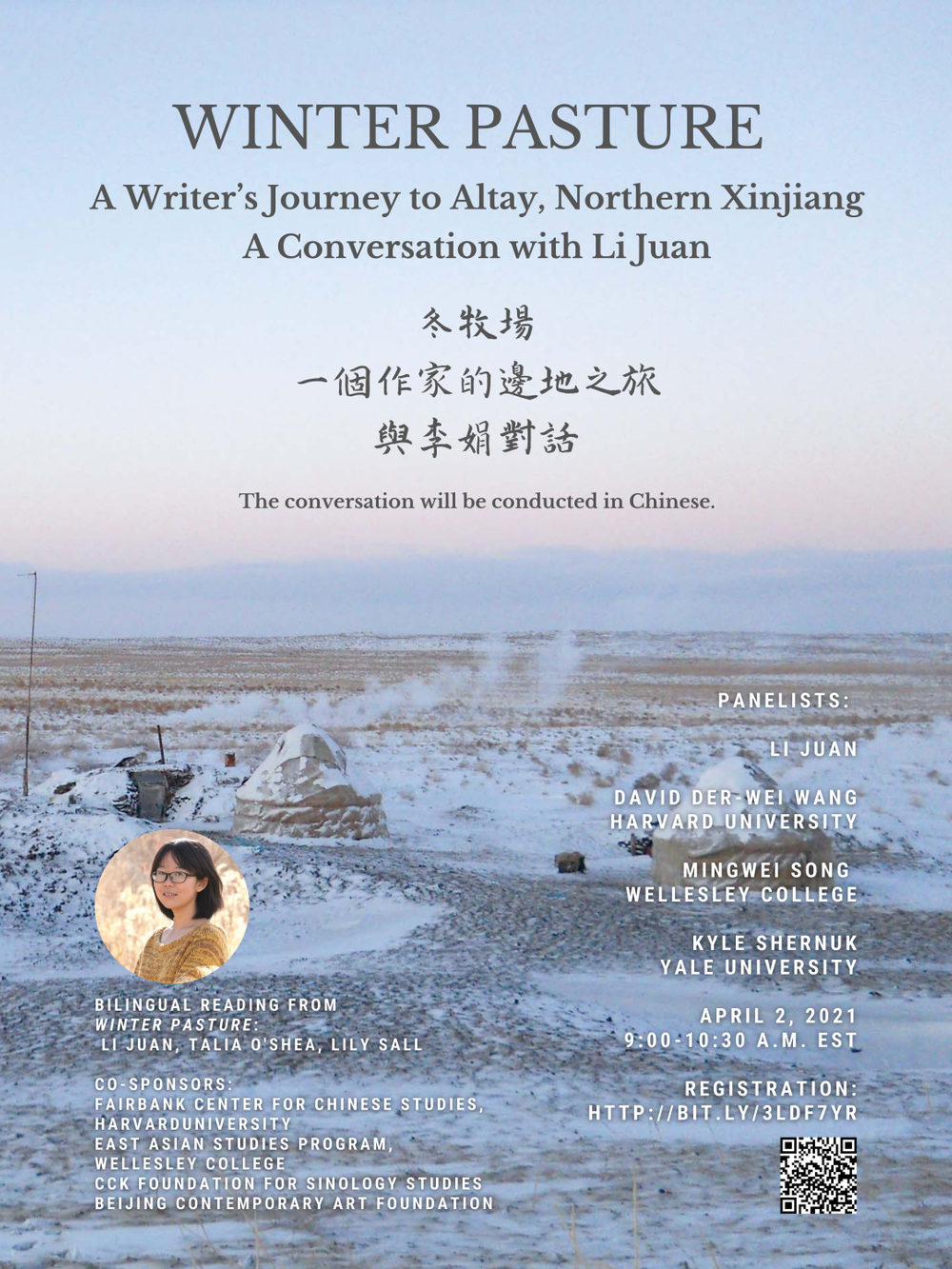

The English translation of this book, Winter Pasture: One Woman's Journey with China's Kazakh Herders, was published in the United States on Feb 23rd, 2021, by Astra Publishing House.

Honored to support the publicity of this book, Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation (BCAF) initiated and co-founded the online panel discussion, "A Writer's Journey to Altay, Northern Xinjiang: A Conversation with Li Juan," with Fairbank Center for China Studies at Harvard University, Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at Harvard University, Wellesley College, and Yale University.

Honored to support the publicity of this book, Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation (BCAF) initiated and co-founded the online panel discussion, "A Writer's Journey to Altay, Northern Xinjiang: A Conversation with Li Juan," with Fairbank Center for China Studies at Harvard University, Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at Harvard University, Wellesley College, and Yale University.

Scan QR code to watch the recording

Panelists

David Wang

Edward C. Henderson Professor of Chinese Literature at Harvard University, and Academician at Academia Sinica.

Mingwei Song

Associate Professor at Wellesley College, ph.D at Columbia University

Qiao Cui

President of Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation

Kyle Shernuk

ph.D at Yale University

Review of the Panel

Born in Xinjiang and grew up in Sichuan Province, Li Juan has a unique experience of traveling between the Han culture and the Kazakh minority group. In her youth, Juan learned to sew and run a small convenience store with her mother, living in Altay, a town where Kazakh nomads shopped. Later, she worked in a factory in the city of Urumqi. In 2003, she became a civil servant until 2008, when she became a full-time writer. The most famous four of her works are The Sheep Path: Spring Pasture; The Sheep Path: Summer Pasture at the Front Mountain; The Sheep Path: Summer Pasture at the Inner Mountain; Winter Pasture. In Winter Pasture, Juan wrote about her experiences of living with a Kazakh family and traveling with them across the vast northern land during the winter.

"Winter Pasture is a sincere, beautiful, and poetic book. It not only shows the geographic scene of the Altay region but also depicts Kazakh's nomadic life with the closest eyes. The author entered as a passerby, but she immersed herself completely into this experience. It is truly a touching work with an immense depth of introspection." Mingwei Song commented.

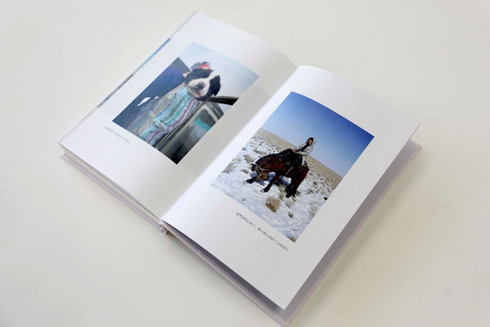

Juan first moved to Altay when she was nine and lived there intermittently for ten to twelve years. Though her physical distance with Altay was always changing, her connection with it was profound. In her thirties, Juan got a chance to work on an individual project under the funding of The People's Literature Magazine, so she decided to come back to the Altay. Living with a Kazakh family, the Cuma family, she helped them take their 30 boisterous camels, 500 sheep, and over 100 cattle and horses across the vast cold land to pasture for the winter.

"Agriculture is hard for the Kazakh people. Nomadism is the easiest lifestyle here, though arduous. People have to migrate like animals. They follow the grassland. When the snow melts in Spring, there's no water in the Gobi Desert, so they have to move to north, following the speed of snow-melting. Across the Ulungur River is the vast spring pasture, suitable for sheep farming. They stay there for a longer period. When the sheep eat all the grasses up, they move to the summer pasture. After staying there for the whole summer, they leave before the first snow. Such an ancient way of life is extremely hard."

Though challenging, Kazakh's nomadic life also reveals their intimate bond with nature. They make accommodation to the way of nature spontaneously, living a sustainable life. However, the Cuma family decided to stop their nomadic life soon. When Juan first joined the Cuma family, she had already heard news about polices of settlement. To settle the herders down is a huge project, but it is gradually happening. Juan said she began to hear news about her past neighbors finding jobs in the cities. To some extent, Winter Pasture recorded the very last actual nomadic life of the Kazakh people.

As a Han Chinese, Li Juan not only experienced a different way of life but also encountered a completely different culture. The Kazakh people are an ethnic minority group in China, while Han people have the most population. "When you enter the Kazakh world alone, it's easier to set aside your stereotypes. After fully immersing in their lifestyle, it's very easy to understand them. It even easy to accept something you never understood before or stood against with." Juan said. The winter pasture experience changed her. It made her softer.

Though immersing herself entirely into the Kazakh lifestyle, Juan was still mindful of her role as an outsider. She recommended the writers also read the works of her friend, Yerkesy Hulmanbiek. "When I was writing, I couldn't help but observe through an outsider's lens and focus on the difference, but Yerkesy is different. She is an insider. She is a Kazakh but wrote in Chinese. That is another cultural lens. Her words are truly brave and touching. Hope you can read her work one day."

Juan expressed she would not go back to live with the Kazakh family again. "Before, I was nobody, just a common villager. But now, if I go back as a writer, it will be hard for me to live with them like before. The change of my role will inevitably influence the way I interact with them."

During the panel, Mingwei Song brought up an interesting anecdote: Once, her friend, Zhou Yi, visited Juan's mom. After hearing Yi was from Shanghai, her mom said, "Shanghai is good, just too remote."

The anecdote offered a brand-new perspective toward cultural differences and relationalities. "Though Xinjiang is at the northwest of China, the most remote region, it is actually the center of Asia." Mingwei pointed out. Xinjiang people always have such a mindset-- no matter how developed the east coast is, they always take their homeland as the center of the world, the land where their forefathers lived.

"How do you write a culture you are not familiar with?" Kyle asked.

"I think no matter who you encounter, as long as you try to understand them, you will find it easy. It needs patience and tolerance, a lot of tolerance, but at last, you will always find them touch you and attract you."

However, Juan's attitude toward cultural difference changes when it comes to language. She took translation as a secondary creation, a process not very relevant to the original work---- "It's my great honor that my work got translated into English, but once it is translated, it's not my work anymore. It is based on my work, but it does not have a strong relationship with me. The barrier of language and culture causes that."

While being asked about the writing style, Juan said she never chose a writing style intentionally. "I just wrote what I saw, heard, thought, and observed. People said I was writing nonfiction. Well, that's just what they say. Without that term, I don't think what I wrote was too much different from fiction..."

"What I wrote is just my memory. I write because I have something that I feel attached to. I would rather say I’m consoling myself than saying I’m creating something new. Yeah. My writing is just for this. Consoling myself."

*Transcribed by Pei Xu, Qianqian Chen

Translated and edited by Elsie Wang