Recap of the “Future Stage” Asia Forum

"Future Stage" is an international research collaboration project exploring various possibilities for performance space in today's connected world. On September 22, 2022 (Eastern Time), the Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation (BCAF) and Harvard University's metaLAB held an online event for the "Future Stage: Asia" forum. Six creators, managers, and scholars from China, Japan, and Korea participated in a two-hour online dialogue, moderated by BCAF Chairman Cui Qiao. Zheng Xiaoyi from iQiyi, Feng Jiangzhou and Zhang Lin from Sifang Art Museum shared their domestic practices, which were enthusiastically discussed by international experts and scholars. Below are some highlights from the conversation.

metaLAB x BCAF

presents

2022 Future Stage Manifesto Panel (China)

Performing Arts in the Post-Pandemic Era

Organizations

Hosts

metaLAB (at) Harvard

Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation

Magda Romanska (USA):

Dean of MetaLAB at Harvard University

Professor of Theater at Emerson College

Editor-in-Chief of theatertimes.com

Cui Qiao (China):

President of Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation

Zheng Xiaoyi (China):

Vice President of iQiyi

Head of Marketing and Public Relations Department

Eiichiro Hirata (Japan):

Professor of Drama Studies at Tokyo Keio University

German Research Institute

Walter Byongsok Chon (South Korea):

Dramatist, Translator, Educato

Associate Professor of Dramatic Composition and Drama Studies at Ithaca College

Kee-Yoon Nahm (South Korea):

Assistant Professor of Drama at Illinois State University

Dramatic Composition at the Illinois Shakespeare Festival

Zhang Lin (China) | Joint statement:

Founder and Production Director of Sifenlv Studios in Beijing and Hong Kong

Co-founder of Beijing TT International Scout Maker Lab

Feng Jiangzhou (China) | Joint statement:

Director of the New Media Professional Committee of China Institute of Stage Design

New Media Artist

Lead singer of The Fly Reggae Band and electronic musician.

#01

Dramatic changes in Asia

· China ·

Zheng Xiaoyi: First of all, thank you very much for the opportunity to share the practices that iQIYI has implemented in the entertainment industry using technology in this new era. iQIYI is an international innovative entertainment platform founded in China in 2010, and is China's leading online streaming platform. Currently, we provide online audio-visual services to audiences in 191 countries and regions, with user interfaces and subtitles available in 12 languages. For us, content production is crucial and is the driving force behind technological innovation.

iQIYI's Huaxia Ancient City Universe is a great example. It represents iQIYI's integration breakthrough in technology and entertainment content. This series starts with the ancient city of Luoyang and will expand to other ancient cities. It is also an example of creating an IP universe, which is a new way of cultural consumption. While building the IP, we also developed digital assets, which cater to the tastes of young consumers and accurately capture the hot spots of youth culture.

By the end of 2020, we had a 1,000-square-meter virtual production base in the Dachang Cultural and Film Industry Park in Langfang, Hebei Province, and the digital assets it produced can be reused, saving costs and opening up unlimited possibilities. In March 2021, we hosted the THE9 XR immersive virtual concert, where LED realistic virtual production and XR technology were simultaneously applied to the live broadcast of the concert, achieving real-time interaction between stars and fans.

"Super Sketch Show" is also a program produced by iQIYI that aims to discover new-generation comedy artists and promote emerging entertainment ecosystems. It has pushed Chinese comedy works into the mainstream market. We have invited various types of theatrical forms to join us, such as sketch comedy, musicals, and silent films, which not only broadened the audience's understanding of comedy, but also brought some outstanding behind-the-scenes scriptwriters to the forefront. At iQIYI, we hope to build a social universe composed of different IPs and use interaction, immersion, and virtual assets to promote new changes.

Cui Qiao: "Super Sketch Show" has entered its second season, and the success of the first season has made us more excited about the arrival of the second season. This is a program that showcases the talents and teamwork of young people. As the producer of this program, what do you think the future of young creative talents in China and even Asia will look like?

Zheng Xiaoyi: Many platforms like ours are working hard to create opportunities for young talent, because we have always hoped to have new breakthroughs in cultural industry production and to use technological means to break through the boundaries of entertainment.

▲ One of the champions of the first season of "Super Sketch Show" Jiang Long (center), starred in the comedy "Dream of the Performing Arts Circle." Image source: iQIYI

· Japan ·

Eiichiro Hirata: Offline theaters have been severely affected during the pandemic, and as scholars, we need to put aside the entertainment industry and focus more on supporting traditional theaters. One of the obvious results of the global pandemic is that the rich get richer while ordinary people do not earn enough income. Therefore, we must first talk about the current situation of theater artists.

Cui Qiao: What is the current funding support for theaters from the Japanese government? Is most of the support for young talent still from private sponsorship? Is there any special funding from the government or international organizations?

Eiichiro Hirata: Since the 1990s, there have been some government subsidies in Japan to support theater artists, which is very good. But since the outbreak of the pandemic and the Tokyo Olympics, we have a new understanding of this policy, which is gradually shrinking and not solely due to the impact of the pandemic. After the Tokyo Olympics, it has become increasingly difficult for artists to apply for funding, and this is also the situation in other East Asian countries. Why do artists have to rely on mainstream activities or commercial performances to make a living? Why do we have to be associated with these high-profit activities?

Cui Qiao: Beijing just hosted the Winter Olympics, and Japan just hosted the Tokyo Olympics. Does mainstream events like the Olympics have a positive impact on the diverse creation of Japanese youth talents? What impact does the production of the opening ceremony of the Olympics have on the creative industry?

Eiichiro Hirata: Of course, it does, and at the same time, the chain effect of the Olympic Games has also provided young people with not only financial assistance but also opportunities to record these moments, which has also earned them some income. But people also overlook the challenges that the theater industry has faced before the Tokyo Olympics.

▲Tokyo Olympics held during the pandemic, image source: Kazuhiro Nogi/Afp Via Getty Images

Cui Qiao: You have published a book about post-dramatic theater. How do you explain this concept?

Eiichiro Hirata: Postdramatisches Theater not only poses creative challenges for artists, but also requires its audience to be more sensitive to things beyond the stage and even in society. The last chapter of this book compares post-dramatic theater to politics because it will arouse the audience's sensitivity to the complexity of the streaming media era.

Magda Romanska: Postdramatisches Theater no longer relies solely on text as its foundation, but rather relies more on visual presentation. As a result, the text becomes secondary, making post-dramatic theater more abstract, conceptual rather than story-based.

▲ "Postdramatisches Theater" by Hans-Thies Lehmann (left); "Theater in Japan" co-edited by Eiichiro Hirata and Hans-Thies Lehmann (right), image source: internet

· South Korea ·

Cui Qiao: As a professional with dual identities as a scholar and creator, how did you establish yourself on the international stage? Recently, Korean works have frequently won international awards such as the Oscars and the Emmy Awards, achieving great success. Can you analyze the reasons behind this phenomenon?

Walter Byongsok Chon: Ms. Cui and I have had deep cooperation on a recent survey questionnaire. We have had conversations with many theater artists. The result is that compared to the popular entertainment industry produced in Korea, the theater industry lags behind these works by a large margin. For example, BTS, a Korean pop music group, the Emmy-winning "Squid Game," the Oscar-winning "Parasite," and many Korean dramas on Netflix and Korean bloggers on YouTube.

What is the reason for this? As someone who grew up in Korea, I have always been taught to pursue success from an early age. This is collective. In the 1950s after the Korean War, Korea was one of the poorest countries in the world, but half a century later, Korean products began to lead international trends. This is closely related to the excessive desire for fame and success, especially in the culture within the entertainment industry. The development of the Korean entertainment industry to its current scale actually took two or three decades. Large companies incubated Korean pop music artists to create content for them, and obtained funding from the government, all of which are important factors for their international success.

Kee-Yoon Nahm: The rise of the Internet has pushed Korean culture towards the international stage. Especially now, our direct cross-border connections are increasingly influenced by the Internet. In the past, people spent many years trying to push Korean culture into the international market. From the 1990s to the early 2000s, Korean dramas also achieved some success in East Asia and Southeast Asia. However, there is a more interesting phenomenon recently. Cultural products like BTS and "Squid Game" did not initially stand out in Korea. Their production companies decided to directly promote them abroad, which resulted in great success. This also led to them becoming popular again in Korea, as Koreans also want to see what kind of works foreigners are interested in. This is undoubtedly a new approach. Previously, a product needed to become popular in Korea before it could begin to explore the international market, but now a Korean pop music idol group or a TV drama or movie can achieve success anywhere in the world before returning to Korea.

▲ Scene from the Korean drama "Squid Game," image source: internet

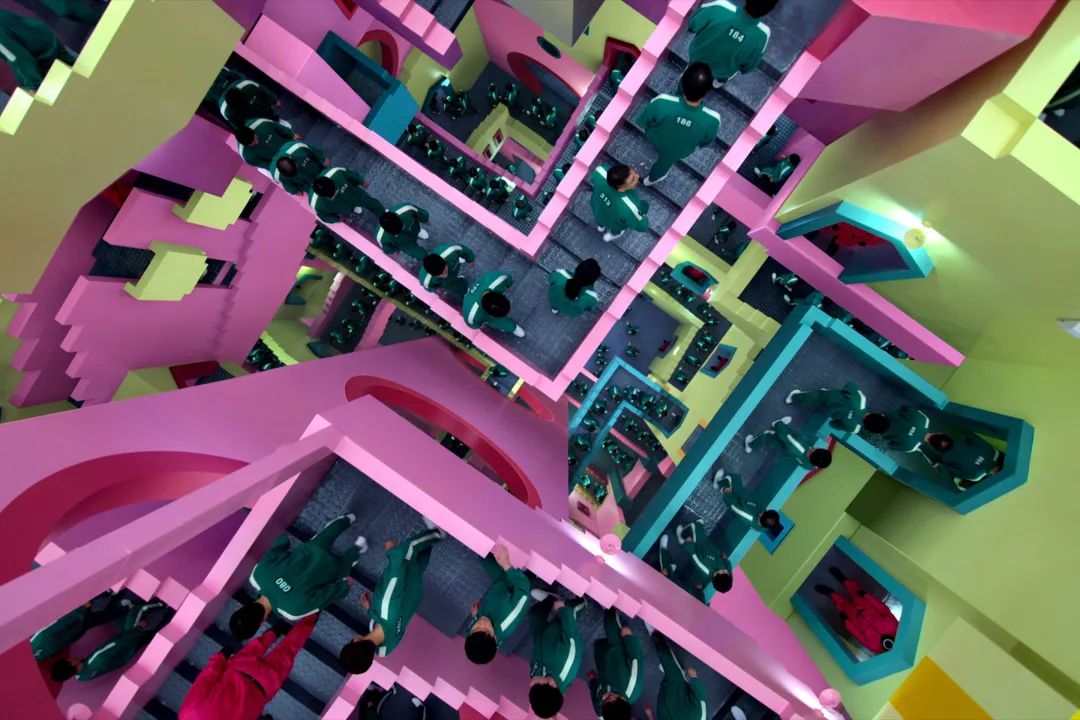

Cui Qiao: Is there a website platform specifically built for independent theaters? Can we see new Korean independent theater works through these platforms? Kee-Yoon Nahm: The theater is indeed conducting some experiments. As Walter mentioned earlier, following the music and film industries, theater has also begun to explore the possibilities of combining technology. This has been particularly highlighted during the pandemic. For example, government-funded theaters have conducted experiments like NT Live. In Korea, a website called playshooter.com has been established for small and independent theaters to showcase their works on a single platform during the pandemic. This is also a new attempt. However, although there are already many works on the platform, it still does not fully cover the diverse ecology of Korean theaters. I don't think there is yet a best solution to create a platform specifically for theater works, like iQiyi or Netflix.

▲ South Korean independent theater streaming site playshooter.com

Walter Byongsok Chon: Musicals were very popular in Korea during the pandemic. Broadway, West End in London, and local Korean musicals all had high viewership during the pandemic. For example, the Korean TV channel Neighbor TV broadcasted a lot of Korean musicals in the early days of the pandemic, which marked the digital transformation of musicals and the expansion of the customer base. But as Kee-Yoon mentioned, for independent theaters, we still have a long trial and error and development stage.

#02

Theater + Technology

Chui Qiao: I know you are the translator of the Korean version of "the Future Stage," and I really appreciate your work. What feedback did young Korean creators have when they saw this manifesto?

Walter Byongsok Chon: The Korean version was published this summer. Ms. Cui and I shared it with many colleagues in Korea. I also asked some professor friends to share it with their students. From our research, there are two feedback directions. First, many people think that the future stage is an innovation, and the theater's entry into digital and online platforms is organic, natural, and inevitable. But at the same time, some people uphold traditional theater. Their fear of innovation mainly comes from: What is theater? And there is a fear that I think comes from the post-war period when contemporary Korean theater is still struggling to find its audience and hopes to connect with more viewers. So can we try new forms and breakthroughs when we have not formed a strong connection with the audience yet?

Chui Qiao: The Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation invited Korean director Lee Chang-dong to direct a short film on "mental health" in collaboration with WHO last year. The lead actress was Jeon Do-yeon, who won the Best Actress award at the Cannes Film Festival. From this experience, we are particularly interested in how Korean film talents grow because many film actors have had experience performing in independent theater groups, and Seoul also has a famous independent theater area. What are the changes and potential opportunities for these young actors, directors, and playwrights due to the huge impact of the pandemic?

▲ Still from the short film "Heartbeat" directed by Li Cangdong, co-produced by Cui Qiao, Chairman of the Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation, image source: internet.

Kee-Yoon Nahm: Like many places around the world, the impact of the pandemic on the performing arts industry has been enormous. Perhaps Korea was relatively lucky in the early stages of the pandemic, as many government-supported theaters were not forced to close, and private and independent theaters could still operate under conditions of ensuring that audiences wore masks and maintained social distancing. The government also provided emergency funding to theater artists, helping many theater groups avoid bankruptcy. In our research with Walter, we found that Korean theaters rely heavily on government funding. Although there are commercial theaters, such as some musical theater groups, most theaters still rely on government assistance to maintain operations due to their long-standing operating model.

Many young artists who are trying to secure funding are actually beginning to think about new fundraising models. How to be self-sufficient and not just rely on government support. This is followed by policy changes and political climate shifts. Around 2016, the Korean government's censorship system for art and theater was embroiled in a scandal that sparked widespread protests. So now there is a lot of discussion about finding stable funding for theaters. Dr. Hirata previously said that the wealth gap is growing, even within the small scope of the art industry. Some theater companies are doing well, but what about the majority of others? Under the impact of the pandemic, many theater groups can only give up and close their doors. The pandemic is certainly a major crisis, but it also makes us reflect on the previous mode of theater operation. For young people, because they do not have the habit of doing things, they have the potential to make changes and try new models for Korean theaters. Funding is certainly one of the problems, but the combination of new media technology and live performances will be the direction explored by these young artists who are not bound by "old" ideas.

Cui Qiao: Japanese director Ryusuke Hamaguchi's new film "Drive My Car" perfectly combines Chekhov's play with independent films. How can we understand this film from different perspectives?

Kee-Yoon Nahm: Pan-Asian cooperation, like some Asian theater festivals, has a long history. Many Korean theater artists will tour in Japan and have good relationships with theaters in Japan and China. Like the movie "Drive My Car," which describes the stage play "Uncle Vanya" (in different languages) in detail, it is like utopia to me, but it is possible. If theater artists from different countries can go to the same place and communicate with each other, even if there are language barriers or cultural differences, new and interesting creations will definitely happen. At present, we are also doing similar things. Even though we are in different time zones and all over the world, we are still in the same space, having real-time discussions, right? We are asking questions and answering questions. So the establishment of such a utopia makes me more willing to support more dialogue and cooperation.

Eiichiro Hirata: During the filming of "Drive my car," the director and team received help from a theater troupe that produces many Chekhov works. At least this proves that the film industry and theater artists can collaborate, but in reality, theater artists face more economic difficulties than those in the film industry. Now, the theater relationships between China, Japan, and Korea are becoming increasingly close, thanks to the artists who understand the importance of this collaboration and work together very well, which is unrelated to politics. Unfortunately, many activities have been put on hold due to the pandemic. So we should continue to launch such activities because artists from China, Japan, and Korea cherish the opportunity to communicate with each other, and this is the result I want to see in this dialogue.

▲ In the film "Drive my car," a deaf actor and a Japanese-speaking actor perform together on stage using sign language. Image source: the internet.

Cui Qiao: Magda, we should create a Youtube account for the Future Stage and hold an online theater festival for independent theater artists.

Magda Romanska: We had an online theater festival that started in 2019 and lasted for three years. In 2020, many people wanted to participate because they were all at home, but we did not have enough technical ability to support it, so we did not continue. The response was very good in 2021, and we decided to do more international theater festivals, cross-cultural, so people can know more about different forms of theater. The theater is often closely related to local culture and can only be performed locally, but by doing it this way, the regional performance may be expanded and mutually influenced. Interestingly, the same script can be interpreted and performed differently in different cultural contexts, receiving different feedback from the audience. We hope to continue this kind of activity next year.

Cui Qiao: Next, we invite Zhang Lin from Si Fen Lv to share with us their practice in technology + theater.

Zhang Lin: Si Fen Lv has made over a hundred works, from classical music to modern opera, from theater space to public living space. We try to find connections with the audience and relations with the market. I want to share three different projects with you. The first project is an electronic digital performance "Live Water" in Nanjing, performed by Feng Jiangzhou himself.

▲ "Live Water" performance, image source: Live Water Weibo official account.

In 2014, we did a performance of "Nightingale" in Jiating Hui, a shopping mall in Shanghai. This was a public space, and although the construction time was very limited, the effect was very good. We did not use professional actors, but invited customers from the mall to perform with 3D glasses. They couldn't see the audience, they saw the image of a game video, and followed random commands to make movements. We combined these visual images, sounds, and virtual experiences to ensure the viewing experience of the performance. After the performance, we quickly set up the scene, costumes, props, and stage decorations for the exhibition hall. Many customers came to "check-in" every day.

▲ Mall customers "performing" "Nightingale", photo source: Sifenglv official website

The final project is "Night Mooring at Qinhuai River" in Nanjing. The most interesting aspect of this performance is that we installed small projectors in every corner of the painting boat. The audience can sit comfortably on the boat and enjoy the holographic projection and the drifting image on the river.

▲Interior rendering of "Night Mooring at Qinhuai River", photo source: provided by guest

▲Interior rendering of "Night Mooring at Qinhuai River", photo source: provided by guestKee-Yoon Nahm: In the performance you just showed in the mall, there seems to be seating around it. Are they real seats?

Feng Jiangzhou: This is the Shanghai Lyceum Theatre, China's first theater, scaled down and placed in the mall.

▲Realistic scene of the performance venue at Shanghai Jiatinghui City Life Plaza, directed and multimedia designed by Feng Jiangzhou, photo source: China Institute of Stage Design official website

Cui Qiao: Feng Jiangzhou used to do hard rock, but now he can combine traditional culture and new media. How do you balance this transition? What is the division of labor between you two (husband and wife)? Zhang Lin graduated from a university in the United States, how do you divide your artistic creation and operational management?

Zhang Lin: My job is to help Feng Jiangzhou with everything he doesn't like to do, or isn't good at. I have to communicate and deal with all sorts of people and things every day to ensure that the project is completed smoothly. Because Feng Jiangzhou is very talented, he needs to focus all his energy on the creation itself.

Feng Jiangzhou: In 2000, I had a choice to make between being a pure artist or a social worker. I ultimately chose to be a social worker. Artists tend to be more focused on personal factors, but I think we should focus more on society. Regardless of whether society is good or bad, we should integrate ourselves into it. That way, we can become social people, not empty people, and interact with many people we don't like or who are completely different from us.

Magda Romanska: I really appreciate this work ("Night Mooring at Qinhuai River") combining Beijing Opera with modern technology and even incorporating Western opera. I teach a course on world theater. In the first class, I always talk about Beijing Opera. I often find that international students from China are not familiar with it, but after the class, they are very happy to share with their grandmothers what they have learned about Beijing Opera, and their grandmothers are also happy that they have gained an understanding of Beijing Opera. My interest in this area also comes from integrating technology into Beijing Opera performances. I often show an immersive Japanese Kabuki performance performed in Las Vegas. Most students only know about popular shows in Las Vegas, but they will discover that traditional performing arts also have a market. After seeing Feng Jiangzhou's work, I want to say that the combination of Beijing Opera and opera itself is already exciting, and the effect he achieved is also very stunning. I'm glad I can see this work.

▲ Performing the classic play "Fight with a Carp" at the live-action Japanese Kabuki performance at the Bellagio Fountains in Las Vegas. Image sources: Las Vegas Review Journal official website (top), teamlab official website (bottom).

Walter Byongsok Chon: Putting performances on a boat, roller coaster or even in a mall like the last one, all provide more immersive space for immersive experiences, and these combinations are fascinating.

#03

Everyone has a Future Stage

Choi Kyu: What does supporting young creators mean in the digital age? How can they establish themselves in the field of digital art?

Kee-Yoon Nahm: In Korea, there are two forms of support for artists during the pandemic. One is project-based, where artists submit proposals and receive support if approved by the government. The other is artist welfare support, which ensures that artists can survive. Last week, a law was passed on labor, artist rights, and sexual harassment.

The "infrastructure" mentioned in the "Future Stage Manifesto" is essential to promoting the boundaries of artistic form in new ways. In our research, many artists have a strong interest in integrating art forms or incorporating new media into live performances. However, the problem is how to get started when the technological threshold is high. Therefore, "infrastructure" has become an important component that enables these new experiments to happen. However, "infrastructure" is not as beautiful as art and can even be a bit monotonous, but it is the part that we need to build. Young artists need to come to a fully equipped space to create, rather than having to gather equipment themselves. They can explore new technologies and "play" with them freely, discovering new things. This is the third type of support, in addition to project-based and welfare support, that I think is necessary.

Eiichiro Hirata: Yes, I completely agree with Kee-Yoon Nahm's perspective, and I'm curious about where we as humanities scholars should focus. The disciplines of technology and science are different from humanities, just like a performance requires a different audience. Historically, there has always been a distinction between technology and art. In the 18th century, European humanities developed from philosophy, where people would discuss art, but it was vastly different from Newton's pursuits. Technology aimed to unify everything, and people needed to be treated equally, disregarding individual differences. So, to this day, artists should focus on this difference. If they don't pay attention to maintaining a distance from technology, their artistic activities can easily become scientific research, erasing humanity. This is also a warning from many scholars.

Cui Qiao: One audience member asked a question about how "The Future Stage Manifesto" focuses on the democratization of the digital world. In East Asia, a challenge is that the elderly tend to be relatively conservative towards new, experimental, and independent things. Do you think digitalization means we can make the elderly community in 10 or 20 years become like Europe or even more advanced?

Walter Byongsok Chon: This is a question about the digital democracy pushing the distance between the elderly and younger generations, and it's possible and optimistic. Society, culture, and every aspect will inevitably follow technology, which is the same for art and artists. However, there is a fundamental discussion about human and cultural authenticity on how art connects with technology. For example, what are the stories that belong to Korea's origin? How do these origins blend together? When it goes out of the country, how can it preserve its Korean identity? How much room is there for development through technological means? This is a gap that needs to be filled from ancient times to the present.

Cui Qiao: When we talk about contemporary theater, we naturally bring up new media. The elderly are always overlooked, and everything is prepared for the younger generation, especially in the business world. But for our "Future Stage Manifesto," democracy represents the potential for the elderly community to become creators. This is an area that no one cares about, and perhaps we should consider it more in the future.

Magda Romanska: Thank you to all the guests. This discussion is excellent, and I hope this is just the beginning. MetaLAB is eager to seize the root of the problem. It's obvious that technology can help people obtain more information, but on the other hand, for example, it's a challenge for the elderly to access technology. The difficulty of accessing technology due to economic differences is a problem we need to solve.

At the same time, how we use these technologies to design our performances is a challenge that artists all over the world will face. A new form of art has already emerged in the fusion, the concept of the metaverse, and online interactive immersion, although we cannot fully define it yet.

The third aspect is the combination of theater and film, and MetaLAB's research also intends to theorize it in different cultures. The pandemic has also accelerated the process of these forms because theater creators at home are thinking about the same thing, which has accelerated our practice of linking technology and performing arts.