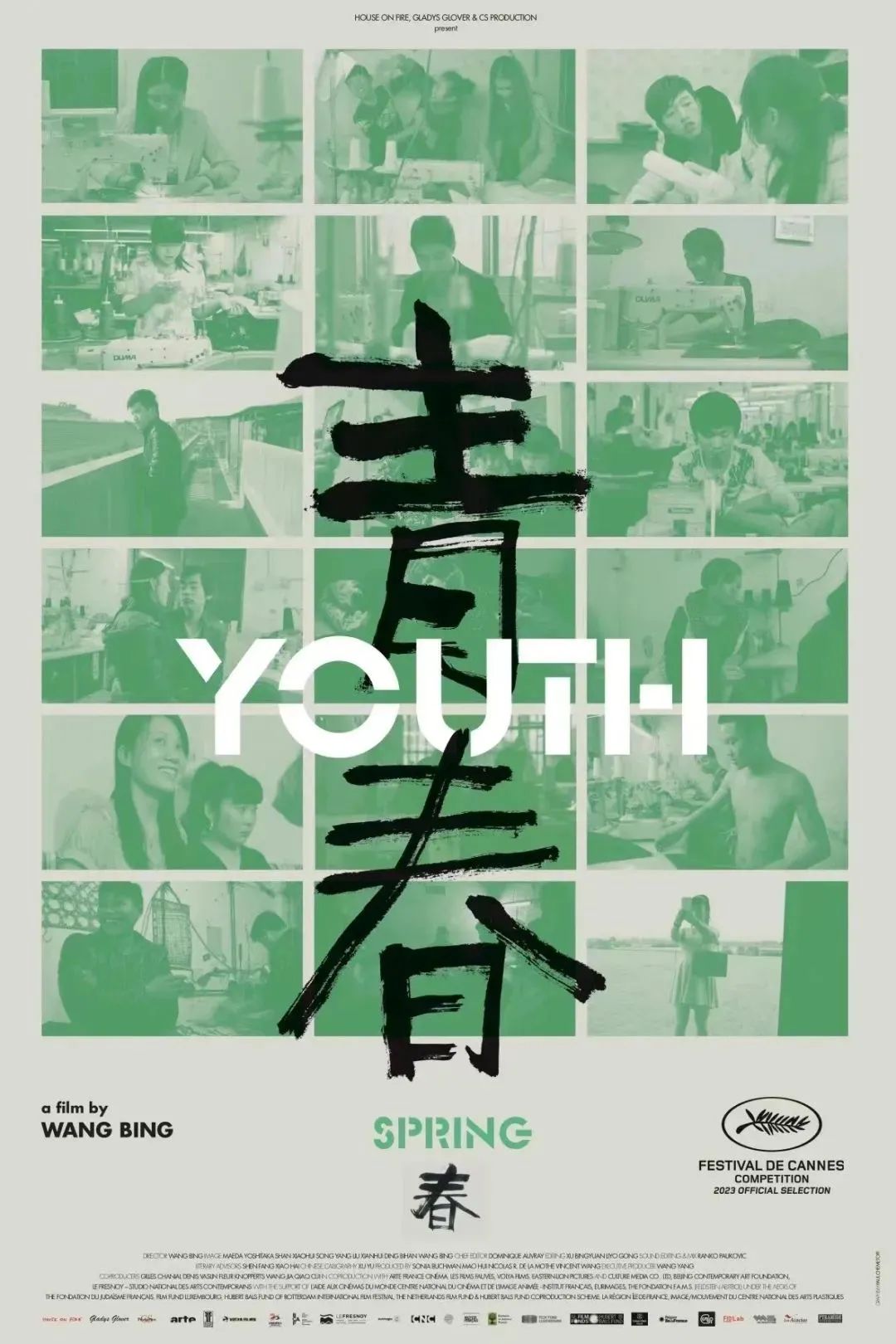

Wang Bing's Youth: Group Portraits of Youth in a Town of Clothing Industry

Youth is a film about the living conditions of young migrant workers. It focuses on Zhili, a clothing industry cluster in the eastern city of Huzhou, 150 kilometers away from Shanghai. In this city dedicated to textile manufacturing, young workers come from all the rural regions crossed by the Yangtze River. They are in their early twenties, share dormitories and snack in the corridors. They work tirelessly to be able one day to raise a child, buy a house or set up their own workshop. Between them, friendships and love affairs are made and unmade according to the seasons, bankruptcies and family pressures.

Here we share with you an interview between film media person Antoine Thirion and director Wang Bing.

#01

First met Zhili

Antoine Thirion: Youth has been some years in the making, and Spring is only the first part. What did you first set out to do, and how did the film blossom into a grand saga?

Wang Bing:My career as a film-maker began with West of the Tracks, which I shot in a giant industrial complex in China’s North-East. From there I moved on to the North-West, with The Ditch, then to Yunnan, in the South-West, for Three Sisters. After that I started thinking about doing something in the area around Shanghai, but I didn’t have anything well defined in mind. Some of the kids I’d met while filming Bitter Money pointed me towards Zhili City, a hub for the garment industry. That was the first time I really traveled around the Yangtze Delta and the whole Shanghai hinterland. I was curious to learn more about its unique character, and I started filming some of the scenes that you can see in this first part of Youth. But there were a lot of obstacles; I’m from the North, I didn’t understand their dialects, and it was hard to make any real contact. Everything was different, the way people lived, how they related and interacted. I soon realized it would take me much longer than on previous occasions to get to a point where I could make a documentary. So I found a place near Shanghai and moved there.

Arriving as a complete stranger in Zhili, I found a checkerboard of streets honeycombed with small garment-making workshops. But I had friends only 60 km away in the historic town of Suzhou, one of whom, a poet, introduced me to some people from Zhili, including workshop managers. One contact led to another, and pretty soon I had the run of the place. I could wander in and out of the factories and dormitory blocks without anyone stopping me or asking me what I was doing there. I never counted the streets, but there are around 20,000 workshops in that one town.

Initially I hadn’t even thought about how many weeks or months of shooting I would need, or how long the film would be. I had enough money to cover six months’ work, but what I found was so intense that I ended up filming there over several years, from 2014 to 2019, amassing 2600 hours of rushes capturing the working lives of a huge cast of characters. In 2018 we started sorting this material, and in the spring of 2019, I decided I had shot enough and the time had come to begin editing. Then Covid hit, and everything stopped, so it wasn’t until 2021, when I came back to Paris, that I was able to start seriously working on the film.

Although I didn’t yet have any clear idea of what sort of film I was going to make, I did know, as early as 2015, that it would focus on Zhili and radiate out from there. I also wanted to travel back with my characters to their home towns and villages, either filming them or just on vacation, which meant traveling up to two thousand kilometers upriver. It was on those trips that I really began to understand life in the Yangtze basin and among the people living on its banks. The film took years to make not just because I shot so much, but also because I needed time to understand the spirit and lifestyles of a region that was foreign to me.

#02

Special sociology in Zhili

Antoine Thirion: This first part is set entirely in Zhili City and ends with the return of a few of the characters to their village. Did you also go for unity of time?

Wang Bing:The textile and garment market is seasonal. Typically, production pauses or stops outright between the end of February and June, and then resumes in July. It’s a bit like the two semesters of a school year. Initially, we therefore shot from September 2014 to June 2015. The last segment of this first part corresponds to the end of the season, when workers go back home.

Antoine Thirion: Does all textile production in China follow the pattern we see in Zhili, or are there any local specificities?

Wang Bing:Before arriving in Zhili, I had visited other garment manufacturing areas in the Yangtze Delta. The size and organization of the workshops varies quite widely, from huge factories to small units and even people working individually at home. In Suzhou, for example, they mainly have these enormous factories with ultra-tight surveillance, where you clearly can’t film. Zhili is on a comparable scale – 300,000 migrant workers come to work there each year – but production is scattered among thousands of small units, individual or family businesses, all of which are self-managed. This means that control and surveillance are also fragmented, making access much easier for a documentary filmmaker.

Antoine Thirion: What is it like in these workshops?

Wang Bing:In terms of general mood, they are all very similar. These are private firms; the working hours are extremely long, from 8 am to 11 pm, with two breaks of an hour each for lunch and dinner. Otherwise, it’s just long hours of work. Workers’ wages are computed on a piece-rate basis, and paid out every six months. The problem is you start making a particular item of clothing without knowing how much each item is going to be paid, that’s something you only find out at the end. In other words, there’s no way of knowing what you’ll get at the end of the season.

Most importantly, however, this industry, especially in Zhili. is not funded by the State, but entirely by private individuals through partnerships and mutual support: in other words, it has its roots in the people, unlike most of the Chinese economy. So it’s really worth studying. In most places, to start a business you need capital, plant and a workforce, you have to pay corporate and local administrative taxes, and so on. Not in Zhili: here you can set up your business in a day. In the morning, you find a workshop, sign a lease on the spot and put up a sign offering work for fifteen machine operators. Everything else you need - machines, materials, fabric - is locally available. Buyers come to your door, and by evening, your finished product can be bundled and shipped out by special convoy to the four corners of China.

This industry’s focus is garment production, but it generates a whole range of other activities, such as transportation, cleaning, maintenance. Until quite recently, the Chinese economy was entirely state- run. Zhili is an example of private enterprise that has vastly expanded, generating its own fascinating sociology. There are forms of primitive organization there that are reminiscent of ancient tribes, with social and economic interactions that can seem quite archaic. In most parts of the world, if you want to go into business, you need to go through the banking system. In Zhili they hardly need banks: trading is based on trust and reputation. Let’s say I’m a business owner and I want to make clothes, and you sell fabric. The problem is, I don’t yet have the money to buy this fabric from you. In a typical modern economy, I would need to get a bank loan. Not in Zhili: I don’t give you a cent, but you let me have the fabric on a deferred payment basis, I start producing the garments and I don’t pay my workers for another six months. And the same goes for my client, who initially doesn’t settle his whole bill, but just a percentage of it, paying me the rest of what he owes once he has sold all the goods, at which point I can pay you back for the fabric you let me have. The whole system operates on this general principle.

▲ Film still from Youth

#03

The formation of Zhili system

Antoine Thirion: What happens if there’s a weak link, if someone defaults?

Wang Bing:That happens, of course, but it’s relatively rare. According to the data, there are 20,000 business owners in Zhili, and in any given year around 400 run off with the money. That’s 2%, not enough to bring down the whole system. This archaic set-up doesn’t exist anywhere else in China, where the other economic sectors are entirely controlled by the State.

Antoine Thirion: How do you explain the emergence and growth of this system?

Wang Bing:Zhili specializes in children’s clothes for the domestic market, 80-90% of which is supplied by the city’s workshops. Quality standards are looser for children’s clothes and styles change fast. Small, nimble units are therefore better suited to meeting this kind of demand than the mass production lines of large garment factories. With so many small production units in Zhili, some can specialize in particular items or styles. Sociologically and anthropologically, it’s a fascinating ecosystem, a kind of micro-society outside the financial mainstream where human relationships have developed very differently. Anyone can start a business with a fairly small initial outlay. In each unit, workers and managers may be exhausted, but they all have a stake in the success of the business. So this is a system where even the poorest can find a place. In a national economy completely controlled by the State and the banks, this type of experiment offers a glimmer of hope or, at the very least, an idea as to a possible way forward. And it’s also in the best interest of local government to keep the system going, as it’s a powerful magnet for jobs and industry. I know of no other place in China where that’s possible.

Antoine Thirion: How could the central government not see this “utopian” model as a threat?

Wang Bing:It may well be tolerated only because it’s contained and unique to this industry. What I’ve described also reflects a fundamental difference between two economies, in China’s North and South. For centuries the Lower Yangtze has been the most highly developed region of China in terms of its trading and commercial culture. That’s what drew me to learn more about the region, its forms of organization and its poetic, literary and aesthetic heritage.

#04

The fate of young workers

Antoine Thirion: Can you tell us a bit more about the sociology of the Zhili workers? How do they end up in Zhili?

Wang Bing:Often whole families - husband, wife, and offspring if old enough to work - travel to Zhili and work together in the same factory. Or a whole group may come, all from the same village; you might find a brother and sister, their parents, and seven or eight of their neighbours all in the same small workshop. The average unit has under 20 workers. Some villages send a lot of workers, some only a few. I didn’t focus on that in the first part of the film, but it becomes clear later when we go upriver to visit the Zhili workers in their home villages in Anhui or Yunnan.

Antoine Thirion: Would you say the life of these young people in Zhili is representative of the whole country?

Wang Bing:Migrant work has been a nationwide phenomenon since the 1990s. The Zhili economy may be atypical, but the lives of these young migrant workers are the same everywhere. They leave home in the spring and head for a big city like Guangzhou or Shanghai to find work, then return the following winter to spend Chinese New Year with their families. That’s pretty much the only time in the year when they’re sure to be home. While they’re away working, no-one’s left in these areas but older people and children; the adults of working age, say 18 to 40, are all in the big cities. But with Covid, things began to change. As jobs became scarcer in the main industrial centers, many potential migrants decided to stay home. This marks the start of a new and still uncertain phase in the country’s development.

Antoine Thirion: How does residence status affect the lives of the workers you filmed?

Wang Bing:It’s key to understanding their situation. Residence restrictions have existed in China in different forms throughout history, but they were officialized and generalized by the party when the People’s Republic was founded in 1949. When I was a child, the residence regime was enforced very strictly. It means you cannot move freely to a town or even a neighbourhood other than the one where you are registered. You may of course take a holiday, or visit friends, but you can’t move house without the government’s permission, which requires completing a long series of complicated formalities. The residence laws therefore confine citizens within a certain radius. At the beginning of the first episode of Youth, Shengnan is pregnant. She’s an only child and her parents don’t want her to leave the family home and take up residence with her husband, they would much rather he moved to their district. Marriage is still the only change of status that allows a change of residence. However, Shengnan’s boyfriend Zuguo is also an only child, so his mother wants to keep him in their family, as they have neither a pension nor health insurance, and a strong young man who can earn his living can no longer support his parents if he goes to live with his wife’s family. This puts the two families at odds, as each of them wants the future groom for themselves.

Obviously, this problem is a direct consequence of the one-child policy that was so strictly enforced in the 1980s and 90s. Residence laws clash with the interests of one-child families: whenever two only- children want to get married, one of the households loses out. The State decides what you are permitted to eat, buy or produce. If you change residence when you marry, you no longer belong to your family, but become part of your spouse’s.

Antoine Thirion: With this system, how can people work away from home for months on end?

Wang Bing:They can leave their villages for work, but only by agreeing to do without essential services, like subsidized healthcare and medication, or access to schools, all of which are subject to local residence registration. This is why the children get left behind, in the villages. And yet, the authorities are still encouraging everyone to go and work in the big cities. There are glaring contradictions within the system, as factories require workers.

▲ Film still from Youth

#05

Film narrative technique

Antoine Thirion: Some scenes give the film a surprisingly lightand cheerful flavour: the custard pie fight in the dormitory, or the constant flirting interrupted by the soundtrack of sewing machines... Were you tempted – or perhaps it was your characters – to inject a dose of fiction into this documentary?

Wang Bing:If some scenes look like slapstick or romantic comedy, it’s just due to the lives my characters lead. I never interfere in their lives or try to direct them in any way. That’s how I see a documentary film: it has to assert reality, tell the truth about people’s everyday lives. These kids are at work nearly every minute of the day. To cheat these long working hours, they constantly play, flirt, pick fights, argue, horse around. They basically have no time off to rest, and they’re not allowed to leave the workplace. So they play music very loud, joke, flirt, squabble, call each other names, or make up games, just to kill time and keep themselves alert. That’s their way of dealing with the situation, of making it more bearable.

Antoine Thirion: And on one of the rare times they can get away, they go and crash in an internet café...

Wang Bing:Only the youngest have any energy left to go to internet cafés, and they still have to start early the next day. You don’t see the older workers going out at night. They spend their time figuring out how many pieces they can turn out in a day, and how much they can earn. Clocking off at 11 pm barely leaves them time to grab some food before going to bed. Most of them only get one day off a week, and in most cases it’s not even that, they’re simply allowed to clock off at 5 pm.

Antoine Thirion: The film seems to unfold as a sequence of 20-minute episodes. Why did you choose to edit it this way?

Wang Bing:I had to find a balance between the multiple workshops and the various groups of workers, who were sometimes very far apart. I couldn’t edit five minutes from one location, then five minutes from another, the end result would have been far too disjointed. So I decided to construct segments of around 20 minutes, each one set in one location and open to a follow-up. The first part of the film has nine such segments, the last one a bit longer, when Xiao Wei leaves Zhili and heads back home to the country. This seemed the best way to avoid too chaotic an edit, while keeping a balance between the different locations. Formally, it’s simpler and more natural. Sometimes, very intense things do happen, but they are concentrated in a few minutes, sometimes even in a few short exchanges.

One of the things I’m happiest with in this film is the spareness of the narrative. In each story, a few words are enough to capture the character’s defining feature, and then the story moves on. On the surface it looks as if life is just unfolding naturally, with no big tragedies, no big dramas; but then you notice this very strong undertow. And when you look closely at what’s at stake for each individual character, and you add up all these lives, you realize that under the casual banter, we’re seeing the destiny of a whole generation in the balance.

Film and traditional narratives often seem to pick an individual out of the multitude of lives around us, like one fish out of the sea, and turn this person into a hero meant to stand for the world. I didn’t want that spotlight effect. I prefer to see all these characters swimming together in the ocean of everyday life, and try to capture something in each of them to suggest the personal difficulties they’re facing and the essence of their individual story. All these workers are living out their lives, often passively, but silently, without comment.

I also wanted to make a film out of independent, self-contained modules, that would allow viewers to make their own connections and build their own narrative, rather than foregrounding any one character.