Qian Junping: Desire is a gift | BCAF New Voice

NEW VOICE

Supporting Young Talent, Sharing Voices for New Dreams

40 potential newcomers in the top 10 creative fields are nominated by 40 Recommender.

The third season of ‘New Voice – A Programme to Promote New Chinese Contemporary Artists’, jointly initiated by the Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation, Caixin Audio-Visual and Caixin Creative, aims to support young talent and share a common dream for the new.

We have invited experts from the fields of art, design, film, architecture, ideas, literary publishing, dance, theatre, music, aesthetic education and other fields to recommend the young creators they are most focused on. They may stand out for their whimsical ideas or bold breakthroughs, or they may have an exceptional sharpness and wisdom, or they may highlight a certain texture that is rare in the present day. Their growth paths and individual choices can also reflect the characteristics of the times. Their pioneering, original, and individual characteristics represent the concept of BCAF's consistent support for authentic expression of ideas and a space for diverse dialogue.

Emerging creators will receive promotional cooperation from BCAF and Caixin Media channels and online media, as well as priority access to international exchange, creative funding, and artistic residency opportunities.

In-depth interview articles and short documentaries on the 10 emerging creators from the third season will be released every Friday from 14:00 starting from March 22, 2024.

NEW VOICE Season 3, Episode 8 |

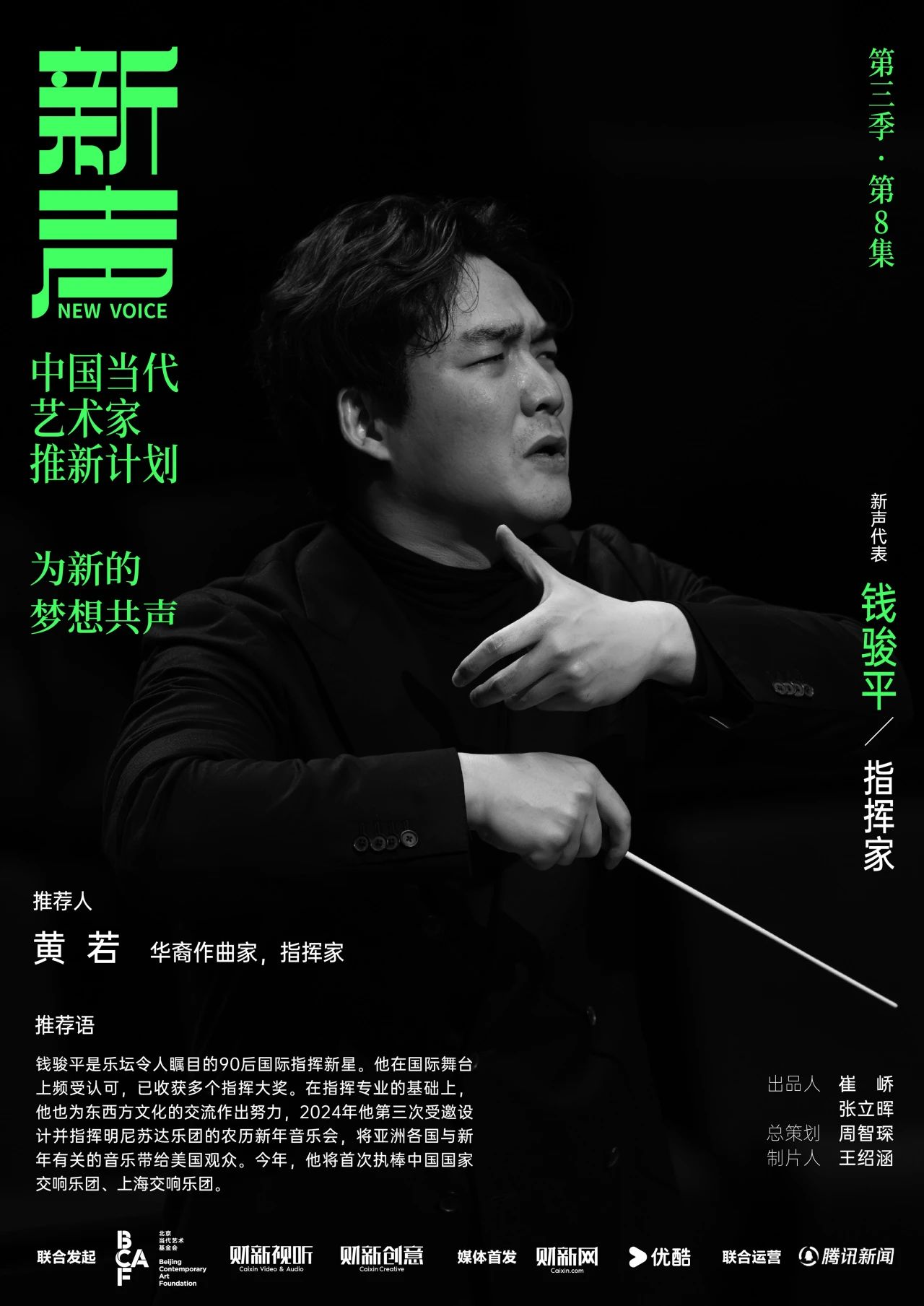

Qian Junping (conductor)

New Voice Recommender

Huang Ruo

composer and conductor

Recommendation:

Qian Junping is a remarkable rising star in the music world, an international conductor born in the 1990s. As a young Chinese conductor, he has a strong sense of music, a powerful presence on stage, and excellent communication skills. He has received recognition on the international stage and has won numerous conducting awards. In addition to his work as a conductor, he is also committed to the exchange of Eastern and Western cultures. In 2024, he will be invited for the third time to design and conduct the Minnesota Orchestra's Chinese New Year concert, bringing music related to the New Year from various Asian countries to American audiences. This year, he will continue to make great strides, conducting the China National Symphony Orchestra and the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra for the first time. We look forward to seeing more of his work in the future!

▲ New Voice, Season 3, Episode 8 | Qian Junping

Qian Junping started learning the violin at the age of five. As he missed the age limit for taking the exam and because the violin is a highly competitive instrument, he had to switch to the viola. There are fewer solo pieces for the viola, which could not satisfy Qian Junping's desire for music. When he was in the third year of high school at the High School Affiliated to the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, students could join the symphony orchestra. After joining the orchestra, Q

‘I always feel that desire is also a kind of talent. You don't necessarily know where it comes from, but when you have the desire to do something, you will have unlimited motivation.’ Qian Junping didn't have a great desire to play the viola, but the viola became the starting point of his academic path and career. With his outstanding performance, he was successfully admitted to the viola major at the Curtis Institute of Music in the United States. Although he wanted to study in the

▲ Artistic photo of Qian Junping during his time at Curtis

When he was a child, he watched the 1999 Vienna New Year's Concert on TV, with Lorin Maazel conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. Halfway through the concert, Maazel started playing his violin. When conducting the Thunder and Lightning Polka, Maazel also played the drums and cymbals next to him, interacting with the percussionist in the back row. He played so hard that he even broke the drum. Qian Junping was fascinated by the sudden sense of humour that emerged from the solemn classical concert. Watching the video, he learned to imitate Maazel conducting the entire concert from beginning to end. Conducting is Qian Junping's strongest desire. From his childhood enlightenment to his current formal conducting career, he has gone around in circles for more than ten years.

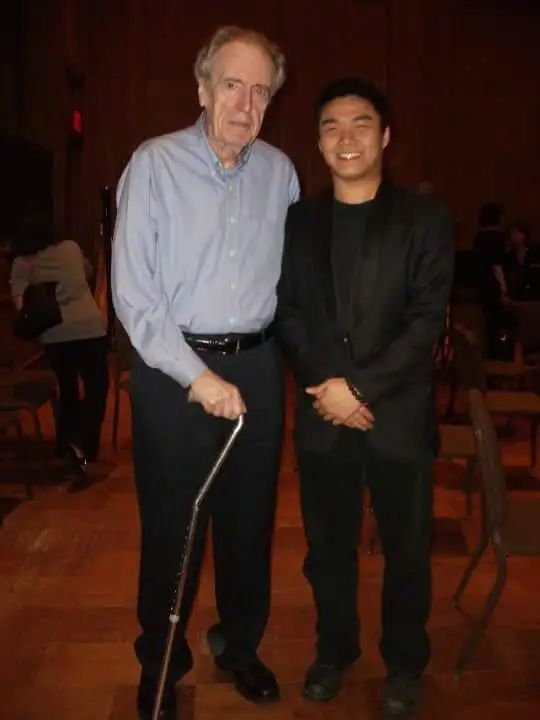

After being admitted to the Curtis Institute, Qian Junping met Otto Werner Mueller, the leading figure in conducting education. He was appreciated by the master and became his last disciple after Mueller retired from the conservatory. Mueller taught him all the common sense about conducting – score reading, conducting methods, counterpoint, etc. Muller did not emphasise technique per se. What had the greatest influence on Qian Junping was Muller's attitude as a conductor. Muller once said, ‘A conductor who goes on stage to rehearse without having prepared the score should be crucified.’ This remark was deeply impressed on Qian Junping's mind. Before every rehearsal, Qian Junping would study the score thoroughly, fearing that he might miss something. As a conductor, the most important things are musical understanding, communication with others and the ability to express oneself. ‘Even through a glance, the orchestra will understand what you mean.’

▲Qian Junping and his mentor Müller in 2020

In order to pursue his dream of conducting, after graduating from Curtis, Qian Junping was admitted to the conducting department of the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music. There, he felt a sense of disorientation as he could not find the same professional atmosphere as at Curtis. He saw that the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra was recruiting viola players, and once again, with the viola, Qian Junping started his career in Europe.

At that time, the music director of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra was the British conductor Daniel Harding. In his spare time during rehearsals, he often sought out Harding to chat and ask for advice on conducting. Harding was under 40 years old at the time, but the musicians in the orchestra had been working for 30 to 40 years. Qian Junping asked Harding, as a young conductor, how he could make the orchestra listen to him. Harding's view was that age didn't mean anything, and that being able to stand on the conductor's platform meant that you had the ability. And as a conductor, you have to constantly challenge yourself to try difficult repertoire and overcome the next difficulty. Harding's pure pursuit of music further inspired Qian Junping's yearning to conduct.

▲Qian Junping and Harding on tour

The musicians in the Swedish Broadcasting Orchestra, on the other hand, seemed to him to be too laid back. The female musicians in the same department had ‘the biggest wish every day to go home early to pick up their children’, while the two male musicians, who were older than him, loved food and fitness respectively. As a young foreigner, he brought a score to work every day and immersed himself in music. After just two months, he was promoted to section leader and seemed to want to become a conductor as well. This was incomprehensible to them. After working in the orchestra for about a year and a half, Qian Junping resigned to focus on conducting.

Qian Junping said of his choices in each period of his life: ‘I care more about the things and people I choose, rather than others choosing me. If it happens that both choices go together, it's perfect. But I won't choose the easy way, or choose passively. I'm not that kind of person.’

In 2015, Qian Junping was admitted to the Hanns Eisler School of Music in Berlin to study conducting. In 2017, he won the Bucharest International Conducting Competition in Romania. From 2018 to 2020, he served as assistant conductor of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra. Now, Qian Junping collaborates with different orchestras around the world every year. The day before our interview, Qian Junping made his debut with the China National Symphony Orchestra, performing Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto in D major and Symphony No. 4 in f minor. Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 4 is a piece that Qian Junping has heard since childhood. During the composition of the symphony, the composer experienced the difficulties of life and the turmoil caused by the war in Russia. His inner struggles and resistance to fate were all written into the melody, and in the end, he found a solution by going among the people to find personal relief. This internal conflict also accompanied Qian Junping for a long time, and classical music has always been the medicine that has accompanied him. He also hopes that through his interpretation, the audience will feel the power of music to soothe the heart.

▲Qian Junping in a performance with the China National Symphony Orchestra

Quick Q&A

Q: What do you think is the most urgent social change that needs to be made?

A: I think that humans are unable to control their selfishness. The world is moving towards de-globalisation, which I don't think is a good thing.

Q: Can your profession help change this situation?

A: Because music does not need language to be interpreted, I think it can somehow connect all human beings.

Q: What personal situation would you most like to change?

A: Sometimes I cannot control and arrange my own work rhythm.

Q: What was the most shocking thing in your childhood?

A: The first time I went to a chorus concert conducted by Mr. Yang Hongnian at the Shanghai Grand Theatre.

Q: If you weren't doing music, what would you be doing?

A: A basketball commentator or an investigative journalist.

Q: Recommend 3 of your favourite classical recordings?

A: It's hard to choose, but I'd say Itzhak Perlman and Martha Argerich's recording of the Franck Violin Sonata, Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic's recording of Mahler's Ninth Symphony, and Carlos Kleiber's recording of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony in Amsterdam.

Q: What do you usually do before a performance?

A: Sleep, as close to the performance time as possible, so that I have enough time to do my hair.

Q: What were you most happy about last year?

A: Losing 20 pounds.

Q: What are the three most important qualities you value as an artist?

A: Truth, goodness and beauty.

Q: Who has had the greatest influence on your career?

A: My teacher Otto Werner Mueller, whom I met when I was studying at the Curtis Institute of Music.

Q: Who are your favourite deceased and living conductors?

A: Living: Daniel Barenboim, deceased: Carlos Kleiber.

Q: What is the piece you would most like to conduct but haven't yet?

A: An opera by Wagner.

#01

His gaze

B: When you first started conducting, you would have a role model to learn from. Who was yours?

Qian: I think my earliest role model was Carlos Kleiber. I imitated him when I was conducting in high school, and I was quite good at it. I can't believe it now. When I was studying at the Curtis Institute, I often went to see the Philadelphia Orchestra perform, and I studied the movements of chief conductor Charles Dutoit. However, the teachers in the conducting department didn't seem to like his style. No one imitated Dutoit, and in the industry, his movements were considered a bit ‘unattractive’. He himself said, ‘I don't want to watch myself conduct.’

B: What kind of development and evolution has there been in the art of conducting since its inception?

Qian: In the beginning, there was no such profession as a conductor, and composers themselves conducted their own works. But after the death of composers such as Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms and Tchaikovsky, their works were still performed. At this time, some people emerged who could understand and read scores, or had the ability to conduct, and the profession of conductor gradually became established. Although composers understand music, it doesn't mean they can conduct. For example, Tchaikovsky was sensitive and fragile, and someone like him might not be suitable for conducting.

B: Are there any rules for conducting gestures? How can one judge a person's conducting technique?

Qian: There is a set of basic conducting movements, such as tapping downwards on the first beat, and a triangle on the third beat. These are all conventions, but everything else is a matter of personal style. Mr. Yang Hongnian once said, ‘When the heart reaches the hands.’ Once you are familiar with these technical movements, you need to explore your inner feelings.

Whether or not a conductor is good still depends on whether the orchestra can read the details the conductor is trying to convey. There is a lot that cannot be expressed in words. A good conductor only needs to stand there and you will play. Just look at him and you will know what the music is like. It is amazing. I once worked with an old Russian conductor, the recently deceased Temirkanov. The old man didn't speak English very well. When we performed Swan Lake, I remember his eyes in particular. He would just look at you, and without saying a word, the whole orchestra would understand and get the right feel for it.

▲In 2012, Qian Junping won the Qingdao Lidelun Conducting Competition.

B: You have had close contact with two conductors, Otto Werner Mueller and Daniel Harding. You met them at different stages of your lives. What kind of influence did they have on you?

Qian: Professor Müller taught me all the common sense and rules of music. He would teach us how to listen to the position of each part in the orchestra in the repertoire. When I get the music score, I can immediately understand which part and passage is important or secondary. Müller taught me a logical way to think about how to run the repertoire, giving me the tools to do so. He completely ignored the technique of conducting. He didn't tell us what to do, but only what not to do.

Reading the score is crucial. Without an orchestra, I have to first put the entire concept of the score into my head, analyse and memorise it myself, and then go to the podium to rehearse. Before I stand on the podium, I need to have digested the score.

His musical values have had a profound impact on me. I always feel that I haven't learned my score well enough, and I can never reach the standard of perfection. I will always feel self-blame, and sometimes I can't sleep, always feeling that I'm not good enough.

Harding is an extremely talented conductor, and he also studied to become a pilot, which shows that he has more than enough intelligence. When it comes to the ‘truth, goodness and beauty’ of an artist, Harding is very truthful. He usually dresses casually, but he has excellent taste. I think that aesthetics is a kind of talent. In Harding's music, tension and beauty coexist, and there is a very elegant expression. These subtle expressions are not rehearsed, but the orchestra will automatically play along with his own temperament. I think this is the highest realm of a musician. This is talent, not something you can fake.

▲Qian Junping performed with violinist Ning Feng and the London Philharmonic Orchestra

B: You often collaborate with different orchestras. How do you work with different orchestras in a limited amount of time?

Qian: My current role is that of a guest conductor. I am not employed by any orchestra and generally accept invitations as they come. The advantage of having my own orchestra is that I can get to know the personalities of each member better, their strengths and weaknesses, and develop a better rapport with them. This allows me to adjust their interpretation to the music I want to create during the rehearsal process.

Now, every time I work with a new orchestra, it's like a new experience. This time, I had only three days of rehearsal with the China National Symphony Orchestra. At the beginning, I would tell them my standards and the effect I wanted to achieve. I also used these few days to get a feel for the orchestra's capabilities. I hope that during the actual performance, everyone will have a positive sense of unity and work together to achieve the desired goal. I don't conduct in a high-pressure manner during rehearsals, but rather I hope to inspire everyone during the performance, so that the orchestra has the desire to do better.

B: How do you inspire?

Qian: I think there are two types of conductors. One is the ‘originator of this music, I represent this music,’ and many conductors don't explain the musical content they want to express. The other is the ‘spokesperson’ for the composer. I may prefer the latter. I will explain why I want to do it and where my basis is. I think this has something to do with the teachers I have encountered. Talking about music with Müller, you get the feeling that he really knows the composers personally. Muller has a basis for explaining why Brahms wrote each note the way he did. One of the abilities of a good conductor is that during the time he is conducting, the orchestra will feel that his approach is the only ‘correct’ one.

#02

Classical music can level the world.

B: Conducting is a form of secondary creation. How do you, as a contemporary, incorporate your own understanding, especially when it comes to many time-honoured classical works?

Qian: After a musical work is composed, it carries the composer's genes, but from then on it has little to do with the composer. When we try to understand and recreate it, we should consider the composer's creative background while objectively and correctly extracting the inherent rules of the work. It's like a director getting a script he wants to shoot. The script is full of tension and special dramatic points, and they all turn into moving images according to the director's ideas.

B: In 2024, you were invited for the third time to plan and conduct the Minnesota Orchestra's Chinese New Year concert. The repertoire for Chinese New Year concerts is usually quite fixed, but this time you included a lot of music from other Asian countries. There are not many Asian faces among overseas mainstream conductors, do you want to change this situation?

Qian: As an Asian conductor, I hope to be seen and valued, and to have a stable career. But in fact, I feel that Asians are still underestimated in the classical music field in Europe and the United States. Europeans and Americans subconsciously still have a deep-rooted colonial mentality, especially because classical music comes from Europe. I think that if classical music is to survive and thrive, it must abandon Eurocentrism. Classical music is just a form and a tool. We need to level the world so that classical music can continue to remain vibrant. I want Western orchestras and audiences to learn as much as possible about Asian culture, and I don't want their understanding of the East to be limited to Chinatowns, Chinese restaurants, or dragon and lion dances.

For nearly a century, Asian countries have been very divided, even though we share many cultural traditions and values. I really hope that music can connect the peoples and cultures of Asia. This Chinese New Year concert will feature music from countries and regions that celebrate the Spring Festival, such as China, Vietnam, and South Korea. I hope to connect Asian cultures across regions.

In 1999, Daniel Barenboim and Edward Said (a Palestinian-American literary scholar) founded the West Eastern Divan Orchestra, which is made up of Israelis, Palestinians and people from other Arab countries. His idea was that in order to play good symphonic music, the musicians must listen to each other, so they must also let go of their obsession with their respective races and beliefs and learn how to coexist with each other. This orchestra has been running for many years and is of a very high quality – and also has a very objective commercial value. Unfortunately, this project also seems futile in the current political situation in the Middle East, and it is difficult to change the current harsh reality. However, I still believe that as artists, we should not stop our efforts.

▲In 2024, Qian Junping will conduct the Minnesota Chinese New Year Concert.

B: Your conducting career has taken you across the Americas, Europe and Asia. What are the biggest differences between these three places?

Qian: In places where the economy is not well developed, such as South America and Eastern Europe, they will generally choose the most conservative repertoire, such as the familiar Beethoven, Mozart, Tchaikovsky and Brahms. In places where the economy is well developed, it depends on the situation. For example, the UK needs to please the market, so if they want to guarantee ticket sales, they need to perform conservative

B: What kind of repertoire is considered challenging?

Qian: Contemporary works, or works that are not considered ‘nice-sounding’. To give an exaggerated but true example, when I was in Scotland, they told me that we could not perform Bartók here because Bartók does not sell tickets.

B: So challenging is relative to the market, not the orchestra or conductor.

Q: Technically speaking, I don't think there is anything that is so difficult that an orchestra cannot do it. Compared to playing the violin, conducting is not about muscles and fingers, but about having a clear mind and the ability to convey and interpret music with your body. In fact, there are some pieces and composers that I like but cannot do, for example, I really like Johann Strauss, but I don't think I am good at conducting the light-hearted waltzes.

#03

Shrinking moment

B: You say you don't listen to much pop music. What kind of inspiration do you think classical music can give to people today?

Qian: The value of music is the live experience. It is a unique existence, and people can gain a unique sense of experience in the live environment. There is a natural sense of ritual in a classical music performance. Classical music has no language, and if you sit there for an hour or two and listen, any experience or feeling you get will be right.

B: What are some of your most memorable music experiences?

Qian: In 2014, I went to the Berlin Philharmonic to hear Simon Rattle conduct Mahler's Second Symphony. When the music reached its climax, I was in tears and cried for half an hour. Another time, I went to Amsterdam to hear Daniel Gatti conduct Bruckner's Ninth Symphony. It was as if I was experiencing some kind of religious ritual, and I even felt like I had lived decades of my life in just an hour and a half. This experience will remain in my memory forever.

▲In 2023, after the pandemic, Qian Junping returned to Scotland for the first time to conduct.

B: What do you imagine the future of classical music to be?

Qian: I think the number of people working in the industry will shrink. It will shrink to a certain point and then stop, because people still need classical music. I think there are too many people working in classical music around the world right now. In the future, there may not be as many people needed, but the best people will remain.

In recent years, the classical music performance market in Europe and the United States has been shrinking. In the United States, for example, classical music used to have very clear social and class attributes. Now, due to generational change, more and more of the ‘old money’ is gone, and the discourse is becoming younger and more equal. If this ‘new money’ doesn't like classical music, there's nothing that can be done about it, right? So the original social attributes of classical music will gradually diminish in the United States. What can be done? I don't know. In Europe, classical music is their culture, and Beethoven is German, just as we talk about our ancient culture. So I think this is the most optimistic thing in Germany. And in Italy, opera is theirs.

B: What advice would you give to young musicians or people who want to become conductors?

Qian: There is no advice. Just find a way to do it. Everyone's starting point and path is different. But if you really want to do it, there's no stopping you.

*The above pictures are provided by Qian Junping

Written by Shao Yixue

Edited by Comfypo Studio

Written by Shao Yixue

Edited by Comfypo Studio