Wang Xiaoqu: Painting is a reflection of magical realism | BCAF New Voice

NEW VOICE

Supporting Young Talent, Sharing Voices for New Dreams

40 potential newcomers in the top 10 creative fields are nominated by 40 Recommender.

The third season of ‘New Voice – A Programme to Promote New Chinese Contemporary Artists’, jointly initiated by the Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation, Caixin Audio-Visual and Caixin Creative, aims to support young talent and share a common dream for the new.

We have invited experts from the fields of art, design, film, architecture, ideas, literary publishing, dance, theatre, music, aesthetic education and other fields to recommend the young creators they are most focused on. They may stand out for their whimsical ideas or bold breakthroughs, or they may have an exceptional sharpness and wisdom, or they may highlight a certain texture that is rare in the present day. Their growth paths and individual choices can also reflect the characteristics of the times. Their pioneering, original, and individual characteristics represent the concept of BCAF's consistent support for authentic expression of ideas and a space for diverse dialogue.

Emerging creators will receive promotional cooperation from BCAF and Caixin Media channels and online media, as well as priority access to international exchange, creative funding, and artistic residency opportunities.

In-depth interview articles and short documentaries on the 10 emerging creators from the third season will be released every Friday from 14:00 starting from March 22, 2024.

NEW VOICE Season 3, Episode 9 |

Wang Xiaoqu (young artist)

New Voice Recommender

Zhang Xiaogang

contemporary artist

Recommendation:

Today, when painting has once again fallen into some kind of embarrassment, Wang Xiaoqu, however, uses her work to anatomically reset the original meaning of images through the secondary processing of various ready-made images, playfully distorting and mutating them wantonly, constantly bringing us surprises. Her paintings not only deconstruct the traditional meaning and linear logic of iconography, but also lead us to explore the hidden ambiguous relationships between people and things in the world through the exaggerated postures of the people in the paintings. In a fictional way, they reveal the collective unconsciousness of human beings, the absurdity of social structure and order, and so on, beneath the surface of the context full of joy. With her unique works, Wang Xiaoqu presents us with a new kind of ‘social portrait painting’ with a distinctive character under a new semantic framework.

▲ New Voice, Season 3, Episode 9 | Wang Xiaoqu

Wang Xiaoqu lived in Chongqing for six years, and studied oil painting at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute for both her undergraduate and postgraduate degrees.

Chongqing is a city of overlapping mountains and buildings, where all kinds of people go about their lives. Wang Xiaoqu likes to wander around the city with her camera.

Ten years ago, she often went to Shibaoti in the centre of Chongqing. Passing through the bustling shopping malls, she would walk to an old neighbourhood with a long flight of stairs. It was a stark contrast to the bustling scene at the top of the hill. This street was full of all kinds of marginal people from society, and it was dark and depressing.

She would also go to Tongyuanju in the old neighbourhood. This was originally the dormitory of the Yangtze River Electric Factory. Due to the decline of traditional industries, this area has gradually fallen into disrepair, like a forest cut off from the world. Almost all the residents here are elderly people.

▲ Chongqing Old Street as seen through the lens of Wang Xiaoqu

Wang Xiaoqu likes to explore these scenes that are hidden in the prosperity of the city, which are both fragmented and contradictory. The people in this environment have ambiguous identities and are full of uncertainty.

She captures these people in paintings with bright colours – a face with love, a man selling colourful balloons, the back of a woman wearing a blue cloth shirt, a plump woman walking a dog in her pajamas... magical, but also present in everyone's lives.

▲ Wang Xiaoqu, ‘Balloon’, 2015, oil on canvas

After graduating from postgraduate school, Wang Xiaoqu followed the trend and moved north. Unlike Chongqing, the people on the streets of Beijing are more vigilant, and Wang Xiaoqu can't just snap photos on the street as she used to. She started collecting all kinds of character images from the internet.

For a while, she saw the story of the mega-rich Mu Zhong in the 1990s. Mu Zhong traded domestically produced canned food for Soviet aircraft, claiming that he wanted to blow up the Himalayas and let the warm and humid air from the Indian Ocean blow north to moisten the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau.

These fantastic stories from the heyday of reform and opening up triggered memories from Wang Xiaoqu's childhood. She is from Guangxi. Her family ran a gift shop, and she often looked through the counter glass at the most fashionable merchandise of the time: all kinds of calendars, product paintings, and image posters.

The indistinct memories overlapped with the stories she saw in reality, and she wanted to recall her childhood memories and the past era through a series of works. Wang Xiaoqu browsed through various public photo albums online, trying to find an abstract image that represented the common paradigm of that collective era.

Her images are dominated by middle-aged men with broad shoulders and round waists, attending various public events – group portraits of men in front of welcoming pine trees, men posing at famous attractions around the world, officials sitting upright around conference tables.

▲ Wang Xiaoqu, ‘Welcoming Pine’, 2018, oil on canvas

Wang Xiaoqu's paintings are full of drama and, like her characters, are unpredictable. She often combines secular scenes in an unconventional way, and every detail on the canvas is her attempt to dismantle past memories and her understanding of the real world.

She describes her creative method as similar to writing a novel: she comes up with the structure, fills it with different content, and then keeps revising it.

She lives in Maquanying on the edge of the city. From time to time, dust fills the air in this urban-rural fringe area, but high-end consumer venues such as equestrian clubs are clustered around it, flaunting the good life in European and American style. The contrast between the artificially created high-end resorts and the poor countryside outside is striking.

Wang Xiaoqu is fascinated by the sense of magic in real life, and she transfers her daily observations and feelings to the canvas – the car with its high-beam headlights rushing towards the stray dog by the roadside on the outskirts of town, the shadowy figure of a cat transforming the trees in the moonlight, and the bamboo forest enveloped in a pink dream.

▲ ‘Escape from the Darkness’, 2024, watercolour and acrylic on canvas

‘I feel that young artists nowadays, I mean those younger than me, are very different from the previous generation. It seems that they focus on very small things and no longer have a sense of responsibility for so-called major themes. I think that's good,’ she says. ’I feel the same way.’

Quick Q&A

Q: What is the one thing about your personal situation that you would most like to change?

A: I feel like I'm living a life that is too removed from the real world. I want to have a more normal life.

Q: What was the first thing you did with the money you earned?

A: In the first grade of primary school, my classmates bought the comics I drew.

Q: To what extent is your current occupation a means of earning a living? If you didn't have to consider survival, how would your work be different from what it is now?

A: Drawing is my occupation. I don't think it would be very different. I feel that my time and personal abilities are limited. I chose to draw because it is the thing that allows a person the greatest degree of autonomy within their capabilities.

Q: What were you most happy about last year and what are you most looking forward to this year?

A: Last year I went to Xinjiang for fun, and this year I will go to Denmark for a creative residency.

Q: What are the three most important qualities you look for in an artist?

A: Honesty, naivety and accuracy.

Q: Who has had the greatest influence on your career?

A: Myself.

#01

Visual forms of our time

B: You are from Guangxi. Did you grow up in an environment with a lot of art?

Wang Xiaoqu: I don't think there is such a thing as art. When I was young, I was exposed to some decorative art, such as decorative paintings. There was a large industry of ink commercial paintings in our area, which is considered more secular art.

B: In your painting ‘Black Cat, White Cat’, the movements of the two cats seem to be taken from the childlike posters that were popular in the late 1990s.

Wang Xiaoqu: Yes. At the time, I wanted to paint a theme related to the reform and opening up, so I used elements from a lot of commercial photography at the time, referencing some calendar photography or poster photography. When painting, I would pay attention to the light and shadow in the calendar paintings. At the time, a lot of the light came from behind, so there would be a very obvious contrast in the outline light.

▲ Wang Xiaoqu, ‘Black Cat, White Cat’, 2019, oil on canvas

B: In your early works, the colours are very bright and mostly monochrome. Where did this choice come from?

Wang Xiaoqu: At the time, I wanted to paint the characters in a way that resembled trademarks or graphic design. I felt that trademarks could be seen everywhere, and that this form of art was related to the environment in which I grew up.

I feel that we have broken away from so-called ancient art, and we don't have so-called modern art with substance. Instead, trademarks are a link between the public and a visual form that can be seen everywhere.

B: What usually prompts you to start a new series?

Wang Xiaoqu: It's probably quite random. What I want to paint is more related to what I'm focusing on at the time. For example, I was interested in the texture of marble for a while, which has a very timeless feel. I would then incorporate these elements into my paintings.

B: Is this sense of the times related to a series of paintings you did previously that were related to the theme of reform and opening up in the 1990s? Why did you pay attention to this historical background at that time?

Wang Xiaoqu: When I was a child, my parents' generation tried to start their own businesses because of some opportunities, but they were not very successful. However, I witnessed the whole process they went through, and it also influenced my growth experience.

I wanted to look at the very strange events of that time, such as a rich man (Mu Zhong) trading cans for an airplane and even trying to blow up the Himalayas. In the end, he was imprisoned for economic crimes.

I had seen a picture before of his company's reception area with many clocks showing the time around the world. I could relate to this in my own creative work. I then painted the space of a hotel lobby, placed a sofa, but then I replaced the sofa with a sea texture and a person swimming in the water.

▲ Wang Xiaoqu, ‘Tides’, 2020, oil on canvas

B: Do you do a lot of preparation in advance when creating? Or do you make adjustments while drawing?

Wang Xiaoqu: The narrative in my series of works is very strong. I make changes while drawing, which is a bit like the way I think when writing. Maybe I come up with some elements today, quickly sketch them out, and then spend a long time revising them. Now when I create, the conception takes a bit longer.

#02

Person in an uncertain state

B: People are a timeless theme in your paintings. Do you often take your camera out with you? What kind of scenes or people attract you?Wang Xiaoqu: Portraits have always been the category of painting that most attracts me. Back in Chongqing, I used to go out and take pictures of people all the time, and it didn't matter if the camera was pointed at someone else. Beijing is very different. Even if you take a picture of someone with your mobile phone, they will point at you and tell you that it's not appropriate. I really like people who are in an uncertain state, when they can't define themselves.

▲ Chongqing street scenes captured by Wang Xiaoqu

B: Do you have any favourite contemporary photographers?

Wang Xiaoqu: I used to go on Douban a lot to look at contemporary photography. I really like the work of Li Zhengde, who photographs very everyday scenes that are also very strange. Feng Li is also in the same genre... Maybe I feel that there is a sense of violence in everything that I find good. My previous works also had a touch of violence.

B: How do you understand this violence?

Wang Xiaoqu: I think it can be felt directly. My paintings always feature people in a collective state, and I think that is a kind of violence. In this kind of social context, you are constantly subject to some kind of collective restraint over the smallest things. You cannot face your own feelings or actions head-on, and you must always discipline yourself according to some collective factors.

B: Is collectivism closely related to your personal experiences?

Wang Xiaoqu: We basically grew up in a collectivist environment. In many cases, I was unable to fully integrate, for example, every time we gathered on the playground to do radio gymnastics, it made me feel miserable.

I have always wanted to break free from this environment, and my current state of life is still not the state of the majority. Sometimes I also feel unsafe. This is a very contradictory thing. I feel uncomfortable when I integrate into the collective, but I also feel unsafe when I am on my own. So these conflicting feelings trigger me to confront my fears head-on in my work.

B: A middle-aged man often appears in your previous series. Who is his prototype? He appears in different scenarios. Where do these scenarios come from?

Wang Xiaoqu: I started working on this series in 2016 and finished it in 2018.

At the time, I went to see works in some mainstream art museums. Generally speaking, the works in these museums are mostly ink paintings and landscape photography, which are quite repetitive. Next to the works, there is always an introduction and a portrait of the artist. This juxtaposition gave me a strange feeling.

In addition, after moving to Beijing, I didn't take many street photos, so I started collecting images from public online albums. Many of these middle-aged men appeared in different landscapes.

I felt that these photos were in themselves a kind of creation, and then I felt that there was some kind of connection between these characters and the mainstream art system. So I painted this series.

I didn't paint specific people; I was looking for an abstract character paradigm, although the material came from different people. He has no direction; he can be like everyone.

B: Where did the inspiration for the later blurry, disproportionate men come from?

Wang Xiaoqu: This is the ‘martial arts’ series. I saw a kind of universal quality that embodies masculinity in photos taken by other people, that is, their posture reminds me of the values of justice and righteousness in martial arts. It's like a shadow left in people's posture.

B: Why are there mainly men in your paintings? Is there an ironic attitude?

Wang Xiaoqu: I didn't have an attacking or ironic attitude when I painted. First of all, the photos I collected were mainly of men. Many photos of public events on the internet mainly show men in the limelight. I also painted some women, but they were more like accessories in the material I collected, and I haven't yet figured out how to paint her.

B: Do you usually finish one series before starting a new one, or do you work on them in parallel?

Wang Xiaoqu: I usually work on them in parallel. At the beginning of the creative process, I don't set out to paint a particular theme. It's only later that I discover some commonalities in the works and then I start to organise them.

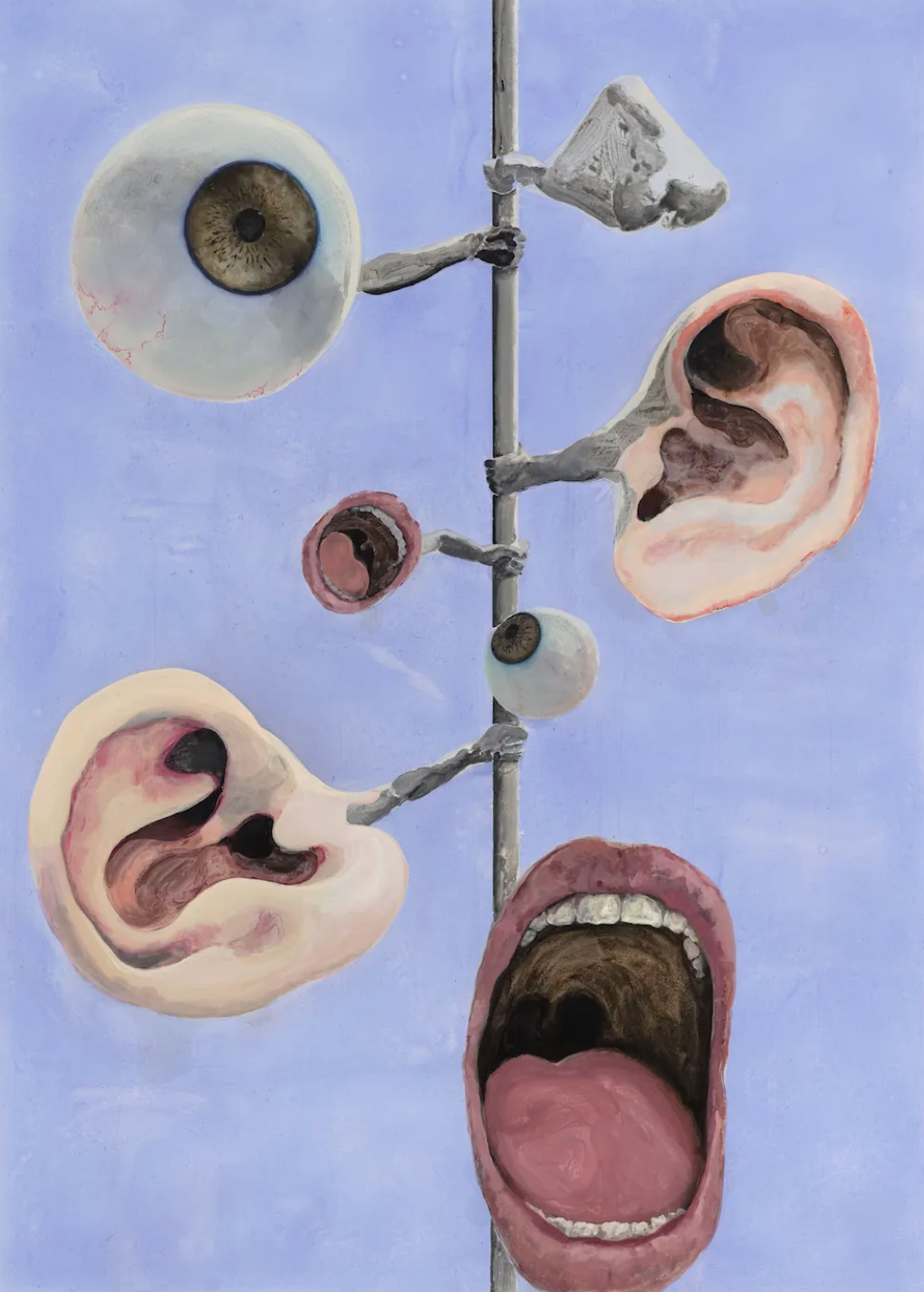

B: In the ‘Signal Tower’ series, why is it the combination of signal towers and various human organs?

Wang Xiaoqu: Actually, this painting is related to the qigong craze. I'm still interested in the topic of collectivity, that is, when a group of people do the same thing in a historical context or cultural trend, it makes me feel very interesting.

Signal towers were a product and symbol of China's technological development and modernization at the time, but at that stage of development, many systems were not yet perfect. For example, the limitations of the medical environment caused many people to heal themselves and start practicing qigong collectively. This was the overlap between people and the development of the times at that time.

▲ Wang Xiaoqu, Signal Tower, 2022, watercolour, acrylic, oil and oil pastel on canvas

B: You seem to be particularly fascinated by the 1990s, from the previously mentioned reform and opening up to the qigong craze.

Wang Xiaoqu: I grew up in the 1990s, so these things are relatively close to me. But now that some time has passed, I have become interested in this distant history.

B: Why is this painting of pansies called ‘Serious Men’?

Wang Xiaoqu: Pansies always grow in clusters, and to me they also look like a group. The pattern of their flowers looks very serious, and it's similar to the collectivist portraits I painted at the time, so I named it that.

#03

What the naked eye can see

B: Your works have a strong sense of social context. Do you often read the news?

Wang Xiaoqu: I don't really pay much attention to it. News is too indirect. I need to see it with my own eyes. The images I paint need to respond to my body. It's not enough just to see it with my eyes. Often, I need to see the people and space in front of me.

I search the internet for a lot of information, but I already have a concept and understanding of these spaces, so I can incorporate them into my creations.

B: What are you working on at the moment? Are you exploring a particular topic?

Wang Xiaoqu: I'm painting scenes related to my living environment. I live in the suburbs, in the middle of nowhere, and I mainly paint things that are within my field of vision.

I now think more in terms of painting, and I don't really try to tackle social topics anymore. I feel that this is too restrictive for painting.

If I want to express a theme, I need to gather a lot of elements to express it. It's like a director – it's actually not fun, and it limits the unknown a bit. This approach is a bit redundant for me. I now want to explore the language of painting more.

▲ ‘Manic Night’, 2024, watercolour and acrylic on canvas

B: How do you understand the language of painting?

Wang Xiaoqu: In the early days, I felt that I had to paint something very objective, something that had some connection with reality.

Now, when I paint, I think about how to organise each line or each surface on the canvas. Things like the structure of light and shadow, proportions and other more basic elements, or a kind of strength on the canvas, are more ‘painting’ to me.

When I paint, I don't really want to achieve a certain effect in the end, but rather I want the whole thing to be in a very free state.

B: So your starting point for painting is changing.

Wang Xiaoqu: I now feel that painting is a form of therapy for me. I often think about what making art means to me. There is no need for it to reflect all of me, it has a certain function, and now it is more of a healing or escape from reality.

Before, my work had a political or narrative element, but I felt that this was too direct and simplistic, and would limit some of the expressiveness within me. I felt that I had reached the edge of a certain range, and now needed to go back a little.

B: How do you understand this range?

Wang Xiaoqu: I feel that there is an unclear boundary between subjectivity and objectivity in painting, and this boundary also affects the degree of initiative I have in my work.

For example, in some periods I try to minimise subjective intervention and let the original dull and rigid shapes appear, or use very glaring colours that I see in reality. However, this suppression of my own initiative makes the painting process very difficult, so I began to pay renewed attention to feelings.

In the process of trying to strip away emotions, I discovered that there are still many personal factors left behind, which belong to the psychological level of the individual and the way they see the world.

*The above pictures were provided by the interviewee

Written and compiled by Shao Yixue

Edited by Studio Comfibo