Writer Cleo Qian: This Is The Life I Almost Had | BCAF Sino-Artists

Writer Cleo Qian: This Is The Life I Almost Had | BCAF Sino-Artists

When we write in a different language, what new horizons do we discover? When we try to find our own voice between a foreign land and our homeland, what obstacles do we encounter? When we want to break through the ceiling of our identity, where should we go?

Starting this week, BCAF launches the "Sino-Artists" series, inviting overseas creators from various fields to share their experiences in studying, living, and creating. With their perspectives, we see a different world with confusion, fear, extreme sadness, and joy.

About Cleo Qian

Cleo Qian is a novelist and poet from California. Her works have appeared in more than 20 publications, winning 2nd place in the Zoetrope: All Story Short Fiction Competition, nominated for the Pushcart Prize and twice longlisted for the DISQUIET Prize, as well as receiving support from the Sundress Academy for the Arts. She is a member of the poetry and performance collective Egocircus.

Cleo graduated from the University of Chicago with a degree in English literature and Political Science, and studied literature at the summer University of Cambridge King-Pembroke Programme. After graduation, she went to Japan to study the language and worked there for two years. She then earned a creative writing MFA from New York University. She has a full-time job at a nonprofit organization. Her other interests, past and present, have included video poetry, clothing and identity expression, melodramas, horror movies, martial arts, and the handmade internet culture of Web 1.0.

Her debut short story collection, LET’S GO LET’S GO LET’S GO, will be published by Tin House in 2023.

Starting this week, BCAF launches the "Sino-Artists" series, inviting overseas creators from various fields to share their experiences in studying, living, and creating. With their perspectives, we see a different world with confusion, fear, extreme sadness, and joy.

About Cleo Qian

Cleo graduated from the University of Chicago with a degree in English literature and Political Science, and studied literature at the summer University of Cambridge King-Pembroke Programme. After graduation, she went to Japan to study the language and worked there for two years. She then earned a creative writing MFA from New York University. She has a full-time job at a nonprofit organization. Her other interests, past and present, have included video poetry, clothing and identity expression, melodramas, horror movies, martial arts, and the handmade internet culture of Web 1.0.

Her debut short story collection, LET’S GO LET’S GO LET’S GO, will be published by Tin House in 2023.

For many born in the 90s, Cleo Qian's writing evokes memories of their childhood: the Japanese manga male protagonist with a fan in hand under the summer sky, the otome games, All About Lily Chou-Chou, Nana...those are nostalgic reminders of the past. It seems like no matter how much the outside world changes, one can still catch their breath by diving into her words.

Cleo was born to immigrant parents from China. From elementary until high school, she would return to Hefei during summers to play with her cousins. When she traveled back to China alone for the first time as an adult, she realized that the China she knew had changed beyond recognition, with QR codes for payments everywhere and more. In an article she wrote for The Guardian, she said that the China she knew was stuck in the 90s, where there were rusted bicycles and motorcycles, sweaty street vendors, and dusty convenience stores with children taking ice cream from the freezer. But these familiar childhood memories are both joyful and surprising to Chinese readers, forming a magical cultural phenomenon.

Growing up in the United States, she not only lived in a cultural gap but also faced similar situations as young people in China, with societal expectations of marriage, children, and buying a house weighing on this generation like an invisible glass dome. After graduating from a creative writing program at New York University she worked at a non-profit organization full-time during the day, writing on nights and weekends. She has a spreadsheet that she has been keeping for a decade, which details her publishing results: on average, receiving 100 rejection letters a year, including a novel she wrote for five years but abandoned. She went through her days like this until her collection of short stories was discovered by the Oregon-based publisher Tin House.

Caught between the experiences of living in the United States and China, the transition from reality to online screens, the conflict between societal expectations and self-awareness, Cleo infused her stories with magical realism. A girl who underwent double eyelid surgery can see everyone's secrets, a karaoke machine that can sing across time and space, a companion lost in an earthquake whose identity cannot be discerned as human or spirit...all pushing the protagonist towards new and unknown worlds.

Her new book, which will be published in August this year, collects the short stories she has written over the past six years and is titled "LET’S GO LET’S GO LET’S GO". It seems like a demonstration by a group of 90s-born individuals, shouting and taking action in the face of so many uncontrollable situations. Despite finally achieving success, Cleo always carries a natural pessimism and awareness: "It sounds like one of those artistic stories of perseverance beyond rejection, but I feel I, and other artists who go through the same, should not have to hope for such a (hard) narrative in the first place."

Cleo was born to immigrant parents from China. From elementary until high school, she would return to Hefei during summers to play with her cousins. When she traveled back to China alone for the first time as an adult, she realized that the China she knew had changed beyond recognition, with QR codes for payments everywhere and more. In an article she wrote for The Guardian, she said that the China she knew was stuck in the 90s, where there were rusted bicycles and motorcycles, sweaty street vendors, and dusty convenience stores with children taking ice cream from the freezer. But these familiar childhood memories are both joyful and surprising to Chinese readers, forming a magical cultural phenomenon.

Growing up in the United States, she not only lived in a cultural gap but also faced similar situations as young people in China, with societal expectations of marriage, children, and buying a house weighing on this generation like an invisible glass dome. After graduating from a creative writing program at New York University she worked at a non-profit organization full-time during the day, writing on nights and weekends. She has a spreadsheet that she has been keeping for a decade, which details her publishing results: on average, receiving 100 rejection letters a year, including a novel she wrote for five years but abandoned. She went through her days like this until her collection of short stories was discovered by the Oregon-based publisher Tin House.

Caught between the experiences of living in the United States and China, the transition from reality to online screens, the conflict between societal expectations and self-awareness, Cleo infused her stories with magical realism. A girl who underwent double eyelid surgery can see everyone's secrets, a karaoke machine that can sing across time and space, a companion lost in an earthquake whose identity cannot be discerned as human or spirit...all pushing the protagonist towards new and unknown worlds.

Her new book, which will be published in August this year, collects the short stories she has written over the past six years and is titled "LET’S GO LET’S GO LET’S GO". It seems like a demonstration by a group of 90s-born individuals, shouting and taking action in the face of so many uncontrollable situations. Despite finally achieving success, Cleo always carries a natural pessimism and awareness: "It sounds like one of those artistic stories of perseverance beyond rejection, but I feel I, and other artists who go through the same, should not have to hope for such a (hard) narrative in the first place."

▲Cleo’s new book. Image from Tin House.

Part 1.

It Was An “Almost” Life

B: Is writing a local character a way for you to access that culture? Or to experience living an alternative live in that local culture?

Qian: This is a question I could spend a long time talking about, but in brief, a lot of my Chinese American peers and I feel a lot of longing for life in Asia. My parents immigrated to the US in the ‘90s. I did spend a lot of my childhood traveling to China in the summers to visit family—which is an experience not all Chinese Americans get. I also grew up around a lot of Asian Americans, and together we all really liked to take pride in East Asian culture; we read Japanese manga, watched Korean dramas, listened to Taiwanese pop music. And when I visited China or watched Chinese movies or read books from Chinese authors, I felt like I was seeing a life I could have had: a life where I didn’t have to feel like such an outsider. I think for me and some of my Asian American peers, we wish for a sense of completeness and belonging that we fantasize we might have had if we were born and raised in Asia. And that life was so close—it was an “almost” life. Like, if my parents didn’t immigrate, that could have been my life.

I’ve read a lot of works by Asian writers in translation. They were really important for my development as a writer. These translated writers did not have to write about race. They wrote about normal, universal human things like work and heartbreak and music and wanting connection. They didn’t have to address things like bilingualism or explaining the Cultural Revolution. I saw a kind of freedom that these “Asian Asian” writers had. If you are a Han Chinese writer born in China and writing in Mandarin, your reading audience implicitly understands you, and that gives you some freedom. As a Chinese American, the reading audience does not implicitly understand you and where you are coming from at all, so in your writing you feel the pressure to explain. I loved reading those works by “Asian Asian” authors because I could feel they had more room to be a full human. And I wanted to have that freedom in my own writing.

Qian: This is a question I could spend a long time talking about, but in brief, a lot of my Chinese American peers and I feel a lot of longing for life in Asia. My parents immigrated to the US in the ‘90s. I did spend a lot of my childhood traveling to China in the summers to visit family—which is an experience not all Chinese Americans get. I also grew up around a lot of Asian Americans, and together we all really liked to take pride in East Asian culture; we read Japanese manga, watched Korean dramas, listened to Taiwanese pop music. And when I visited China or watched Chinese movies or read books from Chinese authors, I felt like I was seeing a life I could have had: a life where I didn’t have to feel like such an outsider. I think for me and some of my Asian American peers, we wish for a sense of completeness and belonging that we fantasize we might have had if we were born and raised in Asia. And that life was so close—it was an “almost” life. Like, if my parents didn’t immigrate, that could have been my life.

I’ve read a lot of works by Asian writers in translation. They were really important for my development as a writer. These translated writers did not have to write about race. They wrote about normal, universal human things like work and heartbreak and music and wanting connection. They didn’t have to address things like bilingualism or explaining the Cultural Revolution. I saw a kind of freedom that these “Asian Asian” writers had. If you are a Han Chinese writer born in China and writing in Mandarin, your reading audience implicitly understands you, and that gives you some freedom. As a Chinese American, the reading audience does not implicitly understand you and where you are coming from at all, so in your writing you feel the pressure to explain. I loved reading those works by “Asian Asian” authors because I could feel they had more room to be a full human. And I wanted to have that freedom in my own writing.

B: Why did you choose to translate Jin Yucheng’s “A Cold Season”? Does it add new layers to your understanding or memories of China?

Qian: I picked up his book when I was traveling alone in China as an adult. It was my first time traveling in China alone. My Mandarin reading ability isn’t that strong, and I actually never finished reading the full novel, but every now and then I try to practice Mandarin by reading. When I found this book in the bookstore, I was really struck by the tone of the first few pages. The sentences are short, but the emotions are so dense. It’s so sorrowful and full of memory. And I am also sorrowful and full of memory, so I wanted to capture the atmosphere in English.

B:Also, what other Chinese writers do you read?

Qian: It depends on what you define as “Chinese,” but in translation from Mainland China, off the top of my head from the last few years I’ve read Yan Ge, Sheng Keyi, Shuang Xuetao, Ge Fei, Xu Zechen, Can Xue, Liu Cixin, and I really liked the anthology That We May Live, especially the story by Dorothy Tse (who is from Hong Kong.)

B: A Chinese friend works in the literary industry once said something interesting: most Asian American writer are not so excited about their work being translated into mandarin or introduced to the Chinese chinese readers, or even have the urge to travel to China for research etc. Do you see this as common?

Qian: I’m not sure…I think Asian American writers are all very different. And someone’s sense of identity can change a lot throughout their life.

Like I said earlier, I tried to explore my Chinese identity a lot from a young age and connect with my family history, and some of my Asian American friends are like me in that desire, and some aren’t. I do wish my writing to be translated into Mandarin so that my family in China can connect with it. I am also very curious what Chinese-Chinese readers would think of my writing, so even this interview with you is very illuminating for me.

I also read a lot of literature in translation—whether from Asia, Latin America, or Europe. So I do hope to be translated into other languages because as a reader, I connect so much with works translated from other languages and cultures. I’m grateful for this interview which might help me connect with a Mandarin audience.

Part 2.

B: A disillusioned man sets up a hidden cinema in a fried chicken restaurant to showcase his own works, a recent graduate girl searches for online strangers to have sex, and four friends embark on a futile social experiment... It seems that the characters in your stories are all trapped. Do you think your debut book explores one general theme such as stuckness?

Qian: It’s interesting that you point out a lot of stuckness in this collection, which other readers have not mentioned. I think it’s very true that my generation – I am a late millennial, almost on the cusp of Gen Z – has experienced a lot of powerlessness and disillusionment. America’s status in the world has changed significantly from what it was during the postwar period and boomer generation. There are impossible amounts of student debt and healthcare costs. There is so much job insecurity, the consolidation of wealth in the top .001%, the hollowing out of the middle class…

I think there is a loss of hope among people in my generation. Boomers could pay off student debt and buy homes and there was a sense of hope: their hard work will achieve the results they want. In my generation, we no longer have that hope. We see so many decaying, anachronistic power structures that aren’t working. Our lives are fundamentally insecure, and many people I know don’t feel like our quality of life will get any better as we age. So there is a feeling that we will have to keep working, striving, and hustling in these insecure conditions, but we don’t have that much control over our lives and are at the mercy and whims of others.

B: I spotted this from your twitter and absolutely loved it (as much as millennials hate to admit), do you think your work explore this generation of stuckness? Or have your style influenced by any millennial literatures?

Qian: I picked up his book when I was traveling alone in China as an adult. It was my first time traveling in China alone. My Mandarin reading ability isn’t that strong, and I actually never finished reading the full novel, but every now and then I try to practice Mandarin by reading. When I found this book in the bookstore, I was really struck by the tone of the first few pages. The sentences are short, but the emotions are so dense. It’s so sorrowful and full of memory. And I am also sorrowful and full of memory, so I wanted to capture the atmosphere in English.

B:Also, what other Chinese writers do you read?

Qian: It depends on what you define as “Chinese,” but in translation from Mainland China, off the top of my head from the last few years I’ve read Yan Ge, Sheng Keyi, Shuang Xuetao, Ge Fei, Xu Zechen, Can Xue, Liu Cixin, and I really liked the anthology That We May Live, especially the story by Dorothy Tse (who is from Hong Kong.)

B: A Chinese friend works in the literary industry once said something interesting: most Asian American writer are not so excited about their work being translated into mandarin or introduced to the Chinese chinese readers, or even have the urge to travel to China for research etc. Do you see this as common?

Qian: I’m not sure…I think Asian American writers are all very different. And someone’s sense of identity can change a lot throughout their life.

Like I said earlier, I tried to explore my Chinese identity a lot from a young age and connect with my family history, and some of my Asian American friends are like me in that desire, and some aren’t. I do wish my writing to be translated into Mandarin so that my family in China can connect with it. I am also very curious what Chinese-Chinese readers would think of my writing, so even this interview with you is very illuminating for me.

I also read a lot of literature in translation—whether from Asia, Latin America, or Europe. So I do hope to be translated into other languages because as a reader, I connect so much with works translated from other languages and cultures. I’m grateful for this interview which might help me connect with a Mandarin audience.

Part 2.

Being A Part of Stucked Generation Influenced My Stories

Qian: It’s interesting that you point out a lot of stuckness in this collection, which other readers have not mentioned. I think it’s very true that my generation – I am a late millennial, almost on the cusp of Gen Z – has experienced a lot of powerlessness and disillusionment. America’s status in the world has changed significantly from what it was during the postwar period and boomer generation. There are impossible amounts of student debt and healthcare costs. There is so much job insecurity, the consolidation of wealth in the top .001%, the hollowing out of the middle class…

I think there is a loss of hope among people in my generation. Boomers could pay off student debt and buy homes and there was a sense of hope: their hard work will achieve the results they want. In my generation, we no longer have that hope. We see so many decaying, anachronistic power structures that aren’t working. Our lives are fundamentally insecure, and many people I know don’t feel like our quality of life will get any better as we age. So there is a feeling that we will have to keep working, striving, and hustling in these insecure conditions, but we don’t have that much control over our lives and are at the mercy and whims of others.

B: I spotted this from your twitter and absolutely loved it (as much as millennials hate to admit), do you think your work explore this generation of stuckness? Or have your style influenced by any millennial literatures?

▲A slide of Millennial Literature from a UCLA student Hannah Janols, Image from Twitter.

▲A slide of Millennial Literature from a UCLA student Hannah Janols, Image from Twitter.Qian: I feel like a common feeling I had over my twenties—and which a lot of my peers relate to—is the feeling of waiting for our lives to actually begin. There is a strong sense of waiting. I think part of this is a generational feeling I described earlier. Our lives just really won’t look like the lives of our parents and there’s not a clear model for this new adulthood.

There’s also a big shift in values where my peers and I don’t necessarily believe in capitalist structures and chasing pure consumerism anymore, and some of us really question traditional family structures. But we also don’t necessarily have a widespread value system that has replaced the previous ones.

I do read some American millennial literature but I think some of my strongest influences are from Japanese literature and film. Although I am not Japanese, I studied the language for a long time and lived there for two years, thinking I might become a literary translator. I was very interested in Japanese modern history, which has, in some ways, presaged similar trends that happened in US society. When I was in college, I attended a translation seminar with Motoyuki Shibata and he said, offhand, that he thinks issues in Japanese society—declining birthrate, isolation, people withdrawing from society like hikikomori and freeters—would be seen in other wealthy democratic nations ten, twenty years later. And he was right!

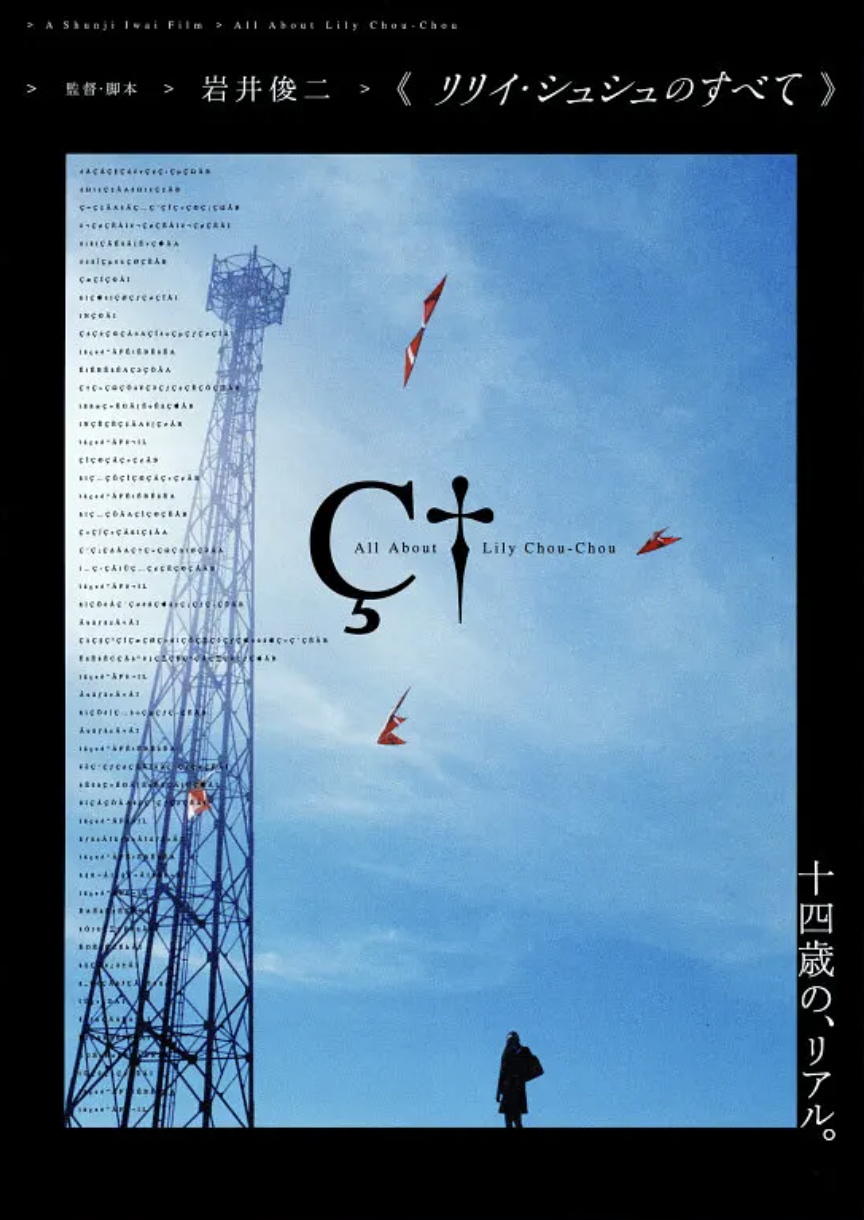

Japan experienced its own economic crisis when the bubble economy popped in the early ‘90s. It was a huge economic change and there’s a whole “Lost Generation” of people who were never able to find stable employment and live the lives of economic empowerment and rising wealth that they saw their parents did. At the same time there was so much technological change and change in consumer identity, telecommunications, the way people relate to each other, as well—and a lot of that has led to increased alienation. You can see the despair, confusion, directionlessness, and ennui young people experienced in Japanese society in the late 90s and early 2000s in movies and manga, like All About Lily Chou-Chou, Nana…they all have characters who are struggling and adrift, whether as teenagers or young adults. I think my generation in America is going through similar existential questions now.

Although I didn’t consciously seek to write about stuckness or what it means to be a millennial in America, I think many of these feelings from this image—economic anxiety, a rootless, anxious life, existential dread—are feelings I had throughout the six years I wrote the book, so they undoubtedly influenced the stories.

▲Movie poster for All About Lily Chou-Chou. Image from Douban

▲Movie poster for All About Lily Chou-Chou. Image from Douban

▲Janpanese comic NANA. Image from Douban.

Part3.

I Try to Hide My Emotional Self in My Writing

B: Let’s talk about short stories in your new book: What’s your favourite short story out of the entire book? Which one took the longest/shortest time to write? Which one took the longest to revise?

Qian: I wrote these stories over six years. The first story in this collection I wrote a draft of in 2016, when I was living in Tokyo. The collection went through several revisions before it was accepted for publication. I took out some stories that were weaker or didn’t fit in with the overall mood. The last story with Luna, “Messages From Earth,” was the hardest—I revised it probably fifteen, twenty times. I lost count. I feel like each story in the book is special and has its place, so it’s hard to say which one is my favorite.

“Chicken. Film. Youth.” is one that feels very close to the lives of me and my peers, and I feel a lot of fondness for the voice and the concerns in it. I also really like “The Girl With the Double Eyelids” for its imaginativeness—I took a long time developing the plot for that story—and for the relationship between the main character and LiLi. I also think “Seagull Village” is a subtle story, and I’m proud of how I crafted the language and descriptions in that story. In each story, I can see some development in my writing craft and I know I changed as writer from story to story, which is also bittersweet.

B: How to understand your evolution as a writer from draft to draft?

Qian: It’s difficult to say exactly. I think some of the earlier stories were more intimate and had a smaller lens, with a microscope on personal feelings. I’m thinking of “Zeroes:Ones” and “We Were There.” Some of the stories I wrote later are more ambitious and imaginative. I wrote more in the third person and experimented more with speculative and surrealist techniques and different ways of portraying narrative. For example, there’s two sections in the story “Power and Control” formatted like a play.

B: Your language has unusual sense of calm and cleanness to it, like someone is retelling a story from memory. Were you conscious of your writing style when you write the stories? Or is intentional about the kind of feeling you want to evoke out of your readers?

Qian: Thank you. That’s very kind. I don’t intentionally set out to write something calm and clean. I’m a very emotional person, and I think I try to hide that in my writing. I admire writers who seem to have a lot of control and who have a cold, cerebral tone, like Natsume Soseki and Patrick Modiano.

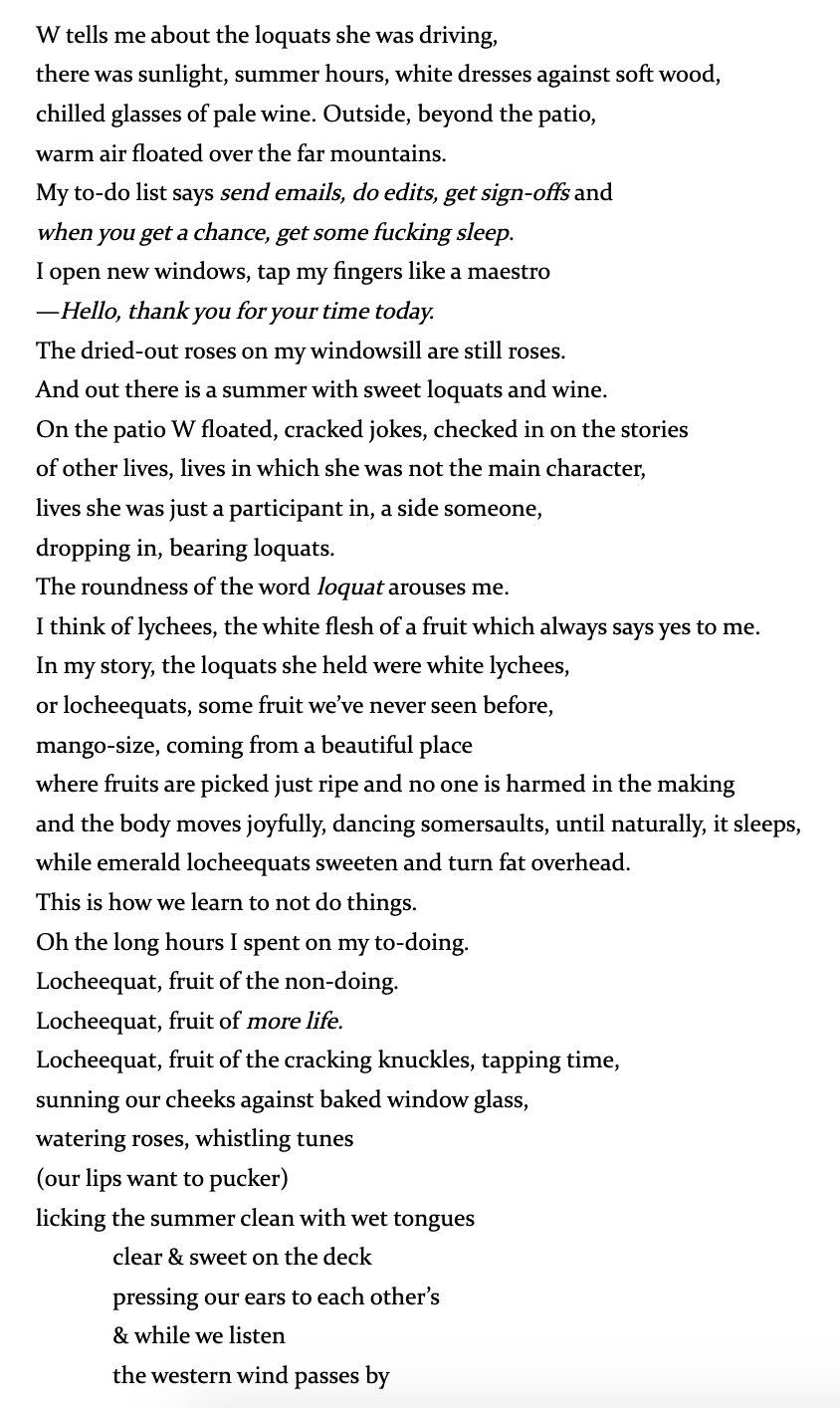

▲poem Iocheequat from The Margins

B: While your writing possess a calm quality, your poetry seem to have more liveness and freedom, especially Iocheequat (fruit of non-doing, fruit of more life), and displays more dense and sharp emotions (vinegar ceremony), or is less confined (a girl on the shore)…Is that intentional? How do you approach poem-writing to fiction writings?

Qian: My poetry is more autobiographical than my fiction. I also feel like I can be more playful in poetry; I’m not sure why. I am not a disciplined poetry writer: I write poetry when I have intense feelings, and sometimes those are joyful feelings and sometimes they are intense anger or intense sadness.

B: What’s the one thing about your current situation you wish to change?

Qian: I wish I had more control over my life and how I spend my time. I wish I had the freedom to not have to be so practical about money and work. I wish the arts landscape in the US were less capitalistic and unequal. I wish the publishing industry here were more equitable. The publishing industry is so much pay-to-play (submissions fees, travel fees, and so on) and requires so much out of you that is not writing.

I always wish I had more time and resources for my art. There are so many books I wish I could write before I die. And I want to try to make other forms of art, too.

Writer: Zheng Ruonan

Wanting to be spotlighted? Contact natalia.yixueshao@gmail.com